Parks for teens: 10 features teens want to see

In many parts of the world, park designers have turned to nature play as a way to foster connections to nature, increase social and cooperative play, and facilitate more physical activity. In many instances, these parks are designed for pre-teen children.

Like more traditional playgrounds, these spaces often exclude teenagers through their design. Yet in a variety of projects facilitated by Growing Up Boulder – a child-friendly city initiative in Boulder, Colorado, USA – teens have requested parks where they feel welcome and that have design features that can integrate them into a broader public sphere. For example, in a participatory process with Junior Rangers involved in Boulder’s open space planning, teens found a city playground at the edge of open space land. Designed for much younger ages, teens found creative means to play with toddler swings and other equipment. In discussion, one of the teens said, “We want parks for teens, too. I am so tired of having moms yell at us.”

10 teen-friendly features:

The City of Boulder’s Parks and Recreation department and Youth Opportunities Advisory Board asked teens what features they would want to see in city parks. This list is also consistent with Growing Up Boulder’s participatory work with teens for public space planning and neighborhood design. Ten of the most consistent features teens in Boulder have requested for public space include:

- WiFi – Teens repeatedly have said they would like a study space with shelter from rain and tables to work in groups. WiFi is a critical aspect of this, as well as for accessing music and other media with phones.

- Movie Nights – Teens like the idea of a central performance space that can show a wide range of movies for all ages and interests.

- Food Trucks and Cafés – From tacos to coffee, teens want access to affordable and diverse food options, representing a variety of cultures and food interests.

- Interactive Lighting and Art – Teens are drawn to interactive spaces, whether they be interactive lights (as found in the New York City’s Pulse Park), or interactive sculptures that allow climbing or play. In response to a solar-powered giraffe sculpture, one teen suggested providing a whole field of African animals that were interactive, such as hippo that spits water or a crocodile to climb on. Importantly, teens not only wanted interactive art pieces (that light or are otherwise playful), but they also wanted places where the public could create the art, such as a graffiti wall, mural wall, or inspirational chalk board with questions such as “What do you love about Boulder?” or “What are your goals?” (Growing Up Boulder 2015).

- Play Spaces for both Children and Adults – Many teens want to play, but do not feel free to do so in playgrounds designed with structured equipment for specific ages. Parks that mix play types are more effective at enabling teen play. For example, at Lizard Log Park, designed by Fionna Robbe in Western Sydney Parklands, Australia, large swings that require cooperation also facilitate more teen play. Other types of play spaces that teens request include fields for pick-up games of soccer or ping-pong tables. Younger teens consistently ask for more active forms of play, such as zip lines or parkour courses that allow risk taking (Growing Up Boulder 2015).

- Study Space – As mentioned for WiFi in parks, teens repeatedly request places where they can hang out and complete school work together outside. These spaces could be simple picnic tables that have some shelter from the elements, a grove of trees with tables and benches, or a tree house for teens. In a public space planning project in Boulder, elementary students wanted a treehouse from which they could read, watch the creek, and listen to birds. At the end of the process, teens also said such a place was important for them, stating: “treehouses are for teens, too!” (Growing Up Boulder 2015).

- Trees, Flowers, Nature – Teens also consistently say that they enjoy being in nature while spending time with their friends. In this case, nature often serves as a backdrop for other experiences, but is appreciated for its aesthetic and restorative qualities, nonetheless. Teens envisioned a study space in a grove of trees, which is part of the City of Boulder’s new Civic Area plan. Like many of the features in this list, teens wanted to see natural features integrated with other functions, such as studying. Some other examples include a koi pond or a pond with colored lights.

- Music Events – In a small neighbourhood park designed for and by teens in Malmö, Sweden, music was an integral feature. The park allows teens to hook up their own phone to a musical system with speakers, lights, and interactive benches, which allow teens to select music, hang out, and dance. There are time and volume limits on these features to respect the neighbourhood’s needs for quiet and darkness at night. At times, we have heard from teens that they don’t go to parks because they are “for little kids.” When we showed them the park from Malmö, they said, “can we have one of those here, too?”

- Lighting and safety features – Teen girls in particular, request lighting and emergency call boxes for safety. This can extend the length of time teens have access to the park and can also provide an enjoyable walk through public spaces instead of going around it during dusk or darkness.

- Water features – Teens repeatedly request features for water play with younger siblings and friends as well as water fountains for sound and visual interest. This can be highly designed fountains, such as the Crown Fountain in Millennium Park, Chicago or simple creek play, with boulders to hop across. Many teens with roots in Latin America particularly like fountain features, which bring a cultural consistency from many Latin American plazas.

Fortunately, many of these features are part of contemporary public space designs. As an example, the City of Boulder’s recent master plan also incorporates many of these features. A challenge is thinking about how to integrate these features into other public spaces and small parks throughout a city so that teens feel welcome wherever they go.

Why parks are important for teens

As the world’s cities become increasingly dense, concerns have emerged at decreasing allocation, types of social interactions, and inclusivity of public space (Day and Wagner 2010, Madanipour 2010). Young people, in particular, are less tolerated in public spaces (Day and Wagner 2010) and can be marginalized in public processes for these spaces (Vivoni 2013). Teen girls, in particular, are isolated from public space (Loukaitou-Sideris and Sideris 2010).

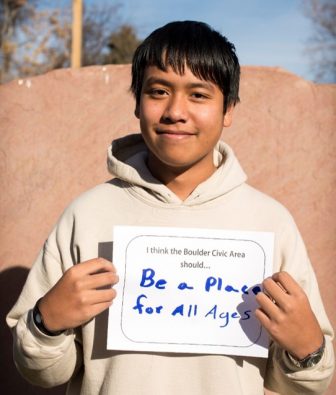

Many people assume that teens want to be separated from the rest of society, but child-friendly research has not found this to be true: teens want to be integrated into public spaces, and they want to see public spaces designed for everyone (Bourke 2015, Breitbart 2014, Derr and Kovács in press). This is particularly significant in the context of adolescent development. When we isolate teenagers from other age groups and parts of society, we increase teen alienation, indifference, dysfunction, and antagonism in the younger generation (Bronfenbrenner and Condry 1970). And it goes against what teens consistently request, which is a place for all ages.

Author: Victoria Derr

References:

Bourke, Jackie. 2014. “‘No Messing Allowed’: The Enactment of Childhood in Urban Public Space from the Perspective of the Child.” Children, Youth and Environments 24(1): 25-52.

Breitbart, Myrna Margulies. 2014. “Inciting Desire, Ignoring Boundaries and Making Space: Colin Ward’s Considerable Contribution to Radical Pedagogy, Planning and Social Change.” In Education, Childhood and Anarchism: Talking Colin Ward, edited by Catherine Burke and Ken Jones, 175-185. Abingdon: Routledge.

Bronfenbrenner, Urie, and John C. Condry Jr. Two worlds of childhood: US and USSR. (1970).

Day, R. and Wagner, F. 2010. Parks, streets and ‘just empty space’: the local environmental experiences of children and young people in a Scottish study. Local Environment: The International Journal of Justice and Sustainability 15 (6), 509-523.

Derr, V. and I. Kovács. How participatory processes impact children and contribute to planning: A case study of neighbourhood design from Boulder, Colorado, USA. Journal of Urbanism: International Research on Placemaking and Urban Sustainability. In Press.

Growing Up Boulder. 2015. Civic Area Participatory Planning: Young People’s Ideas and Views for the Civic Area in Boulder. A Report Submitted to City of Boulder Parks and Recreation, Boulder City Council and Planning Boards. www.growingupboulder.org/ civic-area-2014.html

Loukaitou-Sideris, A., & Sideris, A. (2009). What Brings Children to the Park? Analysis and Measurement of the Variables affecting Children’s use of the Parks. Journal of the American Planning Association, 76(1), 89-107.

Madanipour, A. ed., 2010. Whose public space? International case studies in urban design and development. Abingdon: Routledge.

Vivoni, F. 2013. Waxing ledges: built environments, alternative sustainability, and the Chicago skateboarding scene. Local Environment 18(3), 340-353.

Photo Credits:

Teens on Toddler Equipment (Victoria Derr); A Place for all Ages (Stephen Cardinale);

Main photo by Sharon Mollerus (/www.flickr.com/photos/clairity/149217672/)