How a north London street became a ‘little Netherlands’

Clare Rogers is married with two daughters, aged 13 and 10 and has lived in the outer London suburb of Enfield for nearly 20 years. This three-part article about her experience with the Playing Out movement has been adapted from her talk at Future Cities Catapult in London on 18 January. In the first part of the talk, she speaks about how her own daily journey eventually changed her understanding of our streets.

Until I had kids, and for a while after, I didn’t really think about streets and how we use them. So my street was where I parked my car (as close to my front door as possible), or where I walked from to get somewhere else, like the station or the shops. Unfortunately, it also was and is a cut-through for drivers avoiding the lights in the middle of Palmers Green. (But I used other people’s streets in a similar way, so it was fair enough.) And that’s all my street was.

Then a couple of things happened that totally changed my understanding of streets. Play streets was an idea started, or revived, by a charity in Bristol called Playing Out. I heard about Playing Out in 2011. To turn your residential street into a play street, you applying for a special traffic order from the council, allowing you to close your road to through traffic for up to three hours a month so children can play safely on the road.

Photo: Phil Rogers

Photo: Phil Rogers

It was a fight getting it because some neighbours were vehemently opposed. But a small team of neighbours were eventually able to prove to the council that more residents were for than against, and we were awarded our ‘temporary play street order’. (Here’s my blog post about our eventful first session.)

What’s a street for?

There’s a transformation during play street sessions because there’s no traffic – the whole street becomes a playground. Children go berserk on their scooters or bikes or kicking a ball – inadvertently getting hours of exercise away from any screen.

But there’s a transformation that lasts between sessions too. New friendships have formed between children and adults. Our street has become a community. (We have our own Facebook page, so we must be a community, right?) From only knowing my immediate neighbours a little, I now know more than 30 residents by name; none of us can walk down the street without encountering neighbours who have become friends. Some who had felt isolated found friendship – including a single mum, and a family of new immigrants who were just starting to learn English.

And my perception of the street changed. It became a social space; somewhere to meet and chat to your neighbours. It sowed the idea in my mind that maybe children, or people generally, should take priority over the traffic that passes through the street where they live.

Lost freedom

My play street involvement led me to a conference organised by London Play, a charity that had been instrumental in helping us set up our own play street. The event was at City Hall, January 2013, and it was a pivotal moment for me. One of the speakers was an academic in his 80s called Mayer Hillman. He talked about his London childhood in the war years, a time when children didn’t have much in the way of material possessions, but were free to roam wherever they liked. He pointed out that nowadays children are barely lacking in possessions; many have every device under the sun. But he said this: they have lost their freedom. And those words hit me between the eyes.

It’s true, of course. The image below is from an article written in 2007 in the Daily Mail, by David Derbyshire: ‘How children lost the right to roam in four generations‘.  At 8 years old in 1919, the great-grandfather in this study could roam independently for 6 miles. His great-grandson at 8 years old now can only go to the end of his street: 300 yards. (And for some 8-year-olds I know, that’s quite radical.) How have children lost their freedom? And does it matter? People say often say to me, “You can’t turn back the clock. It’s not the 1950s any more.” But that’s not quite true, because not every country is like ours.

At 8 years old in 1919, the great-grandfather in this study could roam independently for 6 miles. His great-grandson at 8 years old now can only go to the end of his street: 300 yards. (And for some 8-year-olds I know, that’s quite radical.) How have children lost their freedom? And does it matter? People say often say to me, “You can’t turn back the clock. It’s not the 1950s any more.” But that’s not quite true, because not every country is like ours.

The UK response to traffic danger

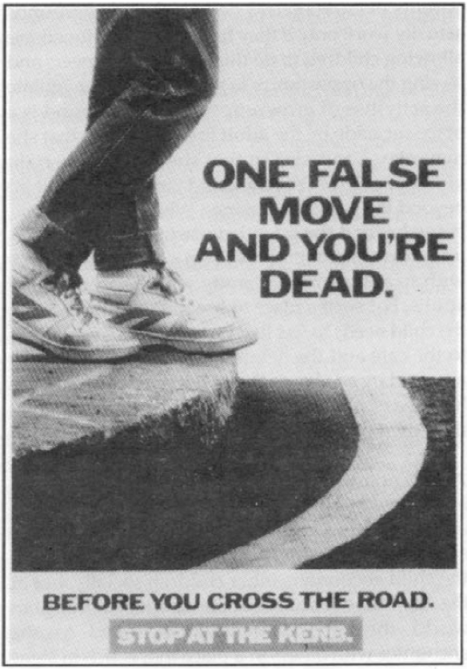

In the 1970s, with traffic growing and road casualty statistics rising, the UK responded by taking children off the road. Mayer Hillman wrote a paper in 1990 called One False Move. He says: ‘in 1971, 80 per cent of seven and eight year old children were allowed to go to school without adult supervision.

By 1990, this figure fell to 9 per cent. Road accidents involving children have declined not because the roads have become safer but because children can no longer be exposed to the dangers they pose’. The title of his paper was

based on government safety advice (right) for children; one poster read, ‘One false move and you’re dead’. The onus was on the child to be careful, not on the roads to be safe.

Meanwhile in the Netherlands…

…a very different response to the rising traffic deaths was going on. 3,000 people died on Dutch roads in 1971, including 500 children. Parents rose up and demanded safer roads with a powerful campaign called ‘Stop the Child Murder’. (See a more detailed account here.)

As a result (combined with other factors), road safety became a top priority, and the network of safe cycle paths we know today began to be installed. Moreover, residential streets were designed to slow traffic and give priority to residents. This means that even today, Dutch children can and do travel independently. I met a Dutch girl in her late teens who told me that at the age of 5 she first cycled alone to the local baker’s to buy bread for her family. For her, it was a moment of real pride – but not at all unusual.

Pic: Dutch National Archive, via London Cycling Campaign

So, the UK’s chidren have lost their freedom to travel and play independently – but does it really matter? Well, apparently it does. The Policy Studies Institute produced a report in 2015 called Children’s Independent Mobility: An International Comparison. It says:

“In 2013, Unicef published a comparative overview of child well-being across twenty-nine OECD and EU countries (Unicef, 2013) …Our report found that there is a positive correlation between Unicef well-being scores and the rank scores measuring children’s degree of freedom to travel and play without adult supervision in these countries.”

In other words, children are happiest in countries that allow them some freedom. So, how do the UK and the Netherlands compare in that Unicef study of children’s well-being? The Netherlands holds 1st place, whilst the UK is at 16th place in a study of 29 developed countries. You decide which is better. To prioritise traffic, and tell children to stay off the road or die? Or to prioritise children, and design roads they can travel on safely?

Air pollution on the road to Damascus

Here’s another fact that has had a huge impact on me. I used to drive my children to school every day (1.7 miles away). One day nearly 3 years ago I was driving on the North Circular having just heard, that morning, the news about air pollution killing Londoners. We now know that the deaths of 9,400 Londoners a year are linked to air pollution – a staggering figure. And much of that pollution is from traffic. As I drove my diesel Volkswagon on an elevated section of the road I looked down across London to my right. It was a beautiful clear, sunny day, but hanging over the centre of town I could see a pale brown haze. I felt sick to the stomach. I thought: I don’t want to be part of this any more.

So, from then on we got the bus or walked to school. We tried cycling once or twice but the girls found the traffic too scary to go on the road, and using the pavements meant getting in the way of pedestrians and bumping up and down every side road. A year later my older daughter started getting the bus to her secondary school. I then followed a friend’s advice and tried out a tandem. It was brilliant. We bought a Circe Helios Duo and I have used it with my younger daughter for the school run ever since. We are both fitter: I’m now cycling at least 8 miles a day. The tandem cost nearly £2,000, but is steadily paying for itself as I save on bus fares and diesel.

And my (then) 9-year-old told me: “Mummy, the only thing that would be better than riding the tandem with you would be riding in a flying saucer with God.” I think she likes it!

What too much motor traffic does to our health

And I began to realise the full extent of what traffic domination has done to us. As well as curtailing children’s freedom and well-being, and damaging our health with its fumes, it has myriad negative effects on our health. For instance, I could spend a whole hour talking about the problem of physical inactivity in this country because we don’t travel actively enough – Enfield has one of the worst rates of childhood obesity in the country, and inactivity in old age shortens lives and worsens chronic health conditions.

So really, there’s nothing wrong with motor traffic dominating our streets… apart from air pollution, mental ill-health, physical inactivity, children’s lack of freedom, lack of community cohesion, serious injury and violent death. Apart from that, it’s fine!

(to be continued)

Clare Rogers

Clare is the coordinator of Enfield Cycling Campaign (the Enfield branch of London Cycling Campaign) and a founder member of Better Streets for Enfield.

This article has been re-blogged from Subversive Suburbanite

What a great idea!!!

What a terrific idea!!