Outdoor play: benefits, influencing factors and actual behaviour of kids

More and more municipalities are, fortunately, working on play-friendly public spaces. However, many policy visions and investments are still based on assumptions made by municipal officials or suppliers of play equipment.

This is partly because good evaluations and effect measurements of existing and new play spaces are scarce, especially where informal play spaces are concerned, writes urban geographer Gerben Helleman, a regular contributor to Child in the City.

And when children are involved, they are often asked about their theoretical wishes rather than their concrete actions. To really gain insight into children’s outdoor play, it is important to look at their actual behaviour. In this article I will share the first results from an ongoing study in The Netherlands. It’s based on a presentation I gave at the Child in the City conference 2022 in Dublin.

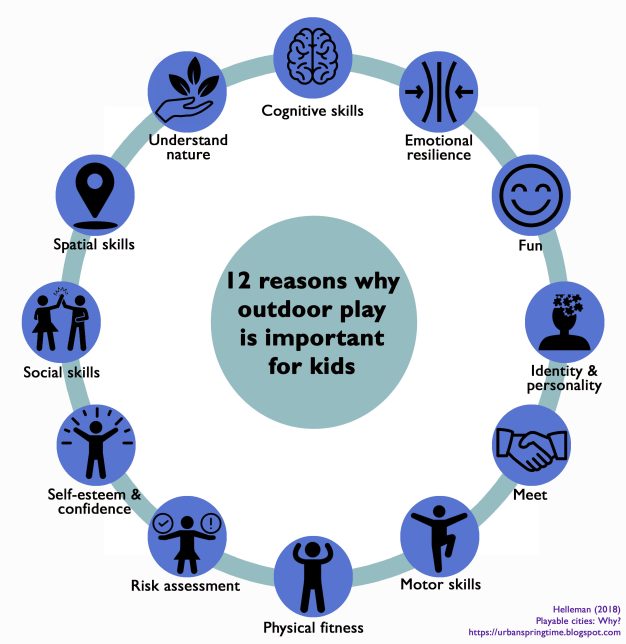

Free play in public space is a unique activity for kids. Without adult intervention they can choose their own location, play form and friends to play with. Based on a literature study (Helleman, 2018), I identified twelve reasons why playing outside is important (see figure). In brief: outdoor play is important for the personal development of kids, for their health, and it is also a lot of fun. You can read more about these reasons in this article: Playable cities: Why?

Despite these benefits, fewer and fewer children are playing outside. Especially when you compare it with their parents and grandparents. Research in the Netherlands shows that 69 per cent of the grandparents played outside more than inside when they were young (Kantar Public, 2018). Nowadays it is only 10 per cent. Instead: of all the kids 53 per cent play more indoors than outdoors.

This is one of the reasons why we have started some research. A research in three neighbourhoods in three different cities in the Netherlands. A research about outdoor play of primary school children (4-12 years old). Our main research question is: which factors can positively influence the use of the outdoor space for playing and how can municipalities make a positive contribution to this?

The research is still ongoing, but we have already conducted a literature research on factors that influence outdoor play behaviour. And we have been counting and observing in public space to find answers to these questions: who plays outside? Where do children play? And what kind of activities are they doing? In the next few months we will also be working together with kids from different primary schools to talk with them about how they experience the public space. And how they fill in the public space for their wishes and needs. We will be doing that with methods like photovoice and walk-along. And at the end of our two years of research we will make recommendations for especially municipalities, but also for urban planners and designers.

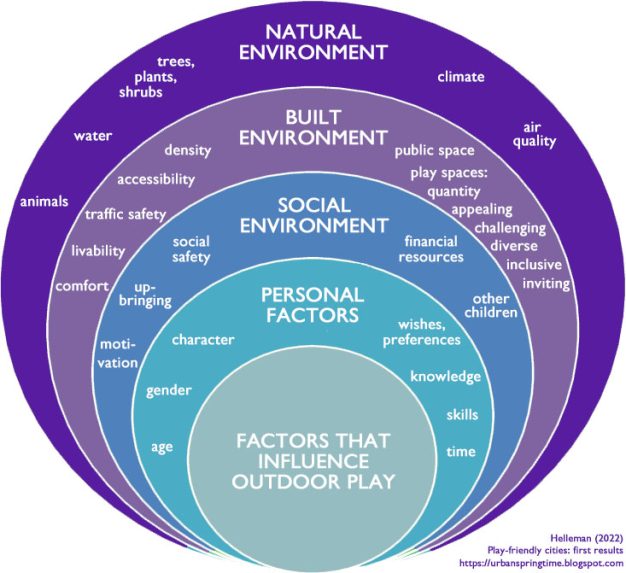

- Personal factors: Age and gender play an important role to what extent children do or do not play outside (discussed further below). The choice of whether or not to play outside also depends on the wishes you have as a child, matching your character and skills. In addition, it is important how much time you have left to play outside freely. You may already be occupied as a kid with homework, training at your sports club or you have to go to day care after school.

- Social environment: Parents can play a decisive role. Do you have parents who encourage you and give you the freedom to do your thing outside (‘freedom to roam’)? Or do you have parents who follow a more protected, sheltered upbringing, because they are more afraid for accidents or the so-called ‘stranger danger’? Money also plays a role. For example, when you have a large bedroom for your own with a lot of toys then you might want to play inside more often. Also important: are there other kids to play with in your street and neighbourhood?

- Built environment: The way we design, arrange and manage our cities has an important influence on whether there are enough public spaces and play areas for children. In addition to the quantity, the quality of the public space and play areas are also important. When they are appealing, challenging, diverse, inclusive and inviting more kids will play there. In addition, it is important that these places are clean, open, accessible, and safe to reach. For example, consider the added value of a good network for pedestrians and cyclist (connectivity).

- Natural environment: Trees are fun to climb in. Plants and water ensure that kids can look for animals. The climate has an influence on the weather conditions: is it too cold, too hot or too wet to play outside? Air quality (i.e. smog) is another factor.

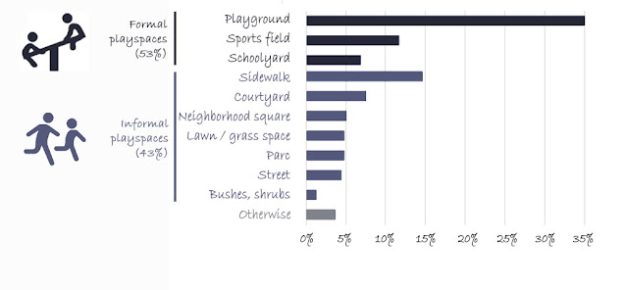

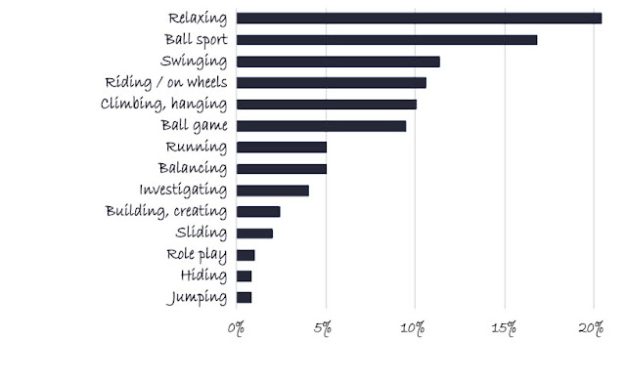

As mentioned before, if you really want to gain insight into children’s outdoor play you have to document the actual behaviour of children. We are doing this in three neighbourhoods in Amsterdam, The Hague and Delft. Each neighbourhood has been divided in smaller areas and these areas are visited multiple times in the afternoon after school and in dry weather. As a researcher you register the location where the child is playing and after observing for a few minutes we fill out a short survey about the who, where and what-questions.

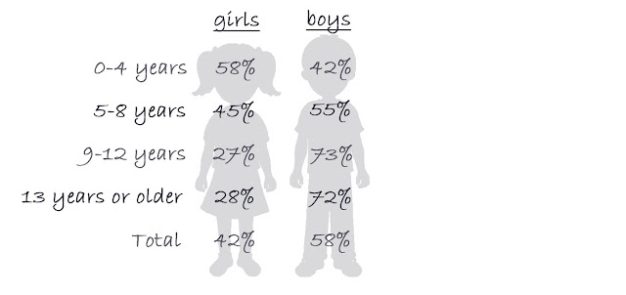

We are only halfway there, but based on 747 observations so far, the first contours are already becoming clear. First of all we have observed slightly more boys (58 per cent) than girls (42 per cent) playing outdoors. This is in line with previous studies in the Netherlands and Belgium.

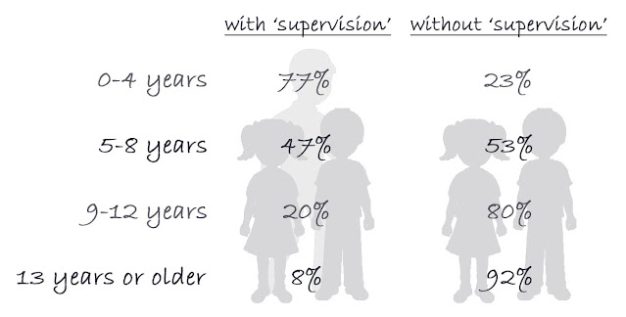

If we look at age, we mainly encountered children between the ages of five and eight (53 per cent) and between the ages of nine and twelve (24 per cent). The ages at which, in general, children play outside more often. At this age they also get more freedom by their parents to play at a greater distance from their own home. This increases their range and options. This is not the case at a younger age. That’s why more adults were physically present among the younger children than among the older children. Most of the times these adults were not there to play with their kids, but to supervise – at an appropriate distance on a bench. In addition, the girls were more ‘supervised’ than the boys. An adult is present in 52 per cent of the observed girls, while this is only 38 per cent for boys.

Observations

The first observation has been noted many times before, but I would like to mention it again: the enormous similarity of our formal play spaces. You see the same kind of slides and seesaws everywhere. Different reasons are often cited as the cause of this uniformity: it must be maintenance-free because this saves costs and it should be safe and vandal-proof. Whatever the reasons, the consequence is that we see the same type of playgrounds in every neighbourhood. Build with little variation or challenges.

Secondly, the trend that I would like to call ‘compensating’. Which means, that almost everywhere we walked, we saw playing attributes that were added to the public space by residents themselves. Possibly due to a shortage of close-by play facilities. Especially the trampolines we come across everywhere. In different shapes and quality. And basketball hoops, swings and plastic slides for small children.

The third observation is about supervision. Parents like to supervise their child for social safety reasons. As we saw before they do this by being physically present at play areas, but they also do this by informal supervision. From their home parents would check every so often to see if everything is alright. This emphasises the importance of clear sightlines to play areas. The famous urban sociologist Jane Jacobs (1961) called it ‘eyes on the street’. I would like to add ‘ears on the street’ to that, because often parents also monitor their children mainly on the basis of sounds. Listening from their balcony, open window or backyard.

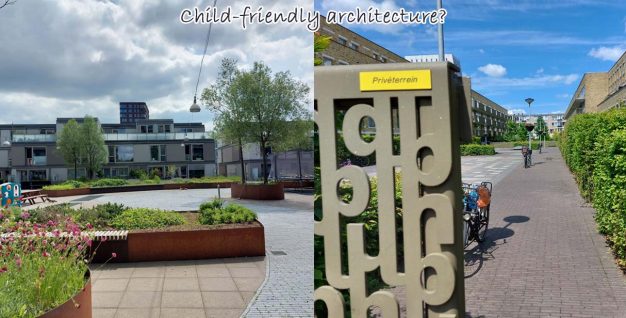

The fourth observation is about the fact that we are losing public space over time. We see that public space and play areas are increasingly closed off. Schoolyards often close their gates after school, so that their playgrounds cannot be used by local residents. But also courtyards that were open for the public in the past are increasingly closed off by means of fences, hedges and signs. And it goes one step further.

Over the past twenty years urban renewal has taken place in some parts of the neighbourhoods. Which means that after the demolition of the multi-family homes and the new construction of single-family homes the former semi-public courtyards are being exchanged for shielded parking spaces, private gardens, or enclosed courtyards with gates to which only residents have the key.

And the last observation is about those new enclosed courtyards. These were designed by architects with the philosophy of child-friendly cities. Children can play safely on their own property with their neighbours. There are no cars and no unauthorised persons. Parents are happy with it because it makes them feel safe. But who really benefits? Maybe we should call it parent-friendly instead of child-friendly? After all, playing outside now takes place in a closed area. For me it is another form of the privatisation of playing, a reserve, a protected area.

Children remain in a certain bubble and therefore do not go on an adventure through their own neighbourhood. In the remainder of the study, we would like to discuss this with the parents and the children.

Gerben Helleman is an urban geographer and researcher in the field of public space and child-friendly cities at The Hague University of Applied Sciences. He is project leader of the above research, and delivered a presentation during the recent Child in the City World Conference in Dublin. He regularly writes on his blog Urban Springtime about urban issues. All images and graphics by Gerben Helleman.

This research is co-financed by Regieorgaan SIA, part of the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO).

Click here for a link to all literary references for this article.