Young children are intuitive urban planners – we would all benefit from living in their ‘care-full’ cities

In an age of climate crisis, unaffordable housing and increasing disparities of wealth, the livability and functionality of our cities are more important than ever. And yet, important voices are missing from urban planning debates — the voices of those who will one day inherit those cities.

According to the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child and the UNICEF child-friendly cities initiative, children of any age or ability have the right to use, create, transform and develop their urban environments.

Despite this, the commonly held view is that preschool children lack the competency to reflect on environments beyond their playgrounds or kindergartens. Young, pre-literate children are denied meaningful participation in city design.

But our work — the Dunedin preschooler study — shows we need to include the voices of these intuitive city planners who think holistically about what a city needs to function well and be safe, healthy and fun.

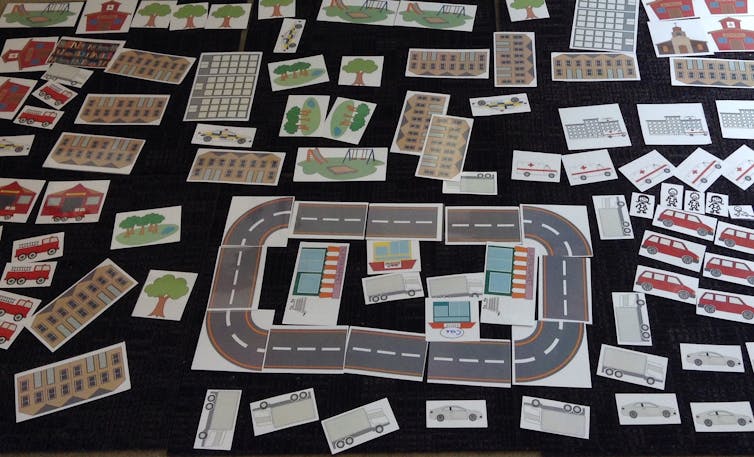

The ‘care-full’ city: how the preschoolers constructed their models.

Author provided

Considerate and thoughtful planners

The project involved 27 children aged between two and five from three kindergartens in Dunedin. The children engaged in a variety of exercises, including mapping their ideal city using picture tiles, and group discussions with researchers.

The children also took us around their neighbourhoods to provide firsthand insights into what they liked and didn’t like about their local area. A very clear picture soon emerged: young children were considerate and future-oriented planners.

The mapping exercise showed children thought about their own needs but also those of other city dwellers and family members. They expected cities to have at least the basic amenities of a child-friendly city.

Read more:

How to teach saving and spending to kids as young as 3 years old

The children wanted health services and facilities that stimulate mind and body, such as libraries, natural environments and gathering places — 78% of children listed playgrounds as important.

While 66% included a supermarket in their design, 59% included a hospital, 48% a fire engine and 41% a coffee shop — as one child observed, their grandma and grandad would use it.

Safety and fun for all

Children also viewed a safe city as important, with 56% placing police cars on their map to symbolise being protected from burglars, “naughty” and drunken people and speeding drivers. They regarded lampposts, pedestrian crossings and traffic lights as essential safety infrastructure.

On neighbourhood walks the children frequently pointed out aesthetically pleasing places — areas with colourful flowers or playful spaces with kōwhai seeds that can be turned into pretend helicopters.

Read more:

World Children’s Day: Young people deserve to be heard during COVID-19

The children also warned us about toadstools, prickly bushes, glass on footpaths or other rubbish they were concerned could hurt animals. One child revealed she “hated the pile of rubbish […] because it can go into the water and kill all the animals when they eat”.

By including the often overlooked needs of non-human things, such as sea creatures and plants, the children demonstrated an awareness of the links between environmental protection, conservation and livability.

Cities as happy places

The children not only created child-friendly cities, but care-full ones that work for all people, animals and plants. Their model cities were safe, socially and physically connected, with destinations, services and amenities available which people of all ages and abilities could get to safely.

More importantly perhaps, they created cities with physical and social elements designed to make people happy.

In creating these worlds for our research, the children showed deep, inclusive and emotional connections. We saw they cared for their local environment and felt a responsibility to all living and non-living things.

Read more:

How gardening at school can tackle child obesity

But children’s voices are still just a whisper in urban and policy debates. This is a shame, because how young people are treated by their city inevitably influences their life chances. Their well-being as young children has obvious implications for being and feeling well later in life.

Our research identifies the need for communities, planners and urban policymakers to ensure young children can participate and help make the most of their cities in a safe, inclusive way.

The challenge for all of us is to develop the right tools for integrating young children’s views, experiences and suggestions. We can then move towards designing more intuitive, care-full cities — ones we would all benefit from living in.![]()

Christina Ergler, Senior Lecturer, University of Otago

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.