How Oslo achieved zero pedestrian and bicycle fatalities, and how others can apply what worked

In 2015, the City of Oslo, Norway, made a commitment after years of rising transportation injuries to reduce car traffic and prioritize the safety of pedestrians, cyclists and the environment.

Unlike in the United States and other countries where transportation fatalities are often viewed as unavoidable, the government of Norway made a strong commitment to eliminate serious injuries and fatalities on their roadways nationally and has worked towards this vision for nearly two decades.

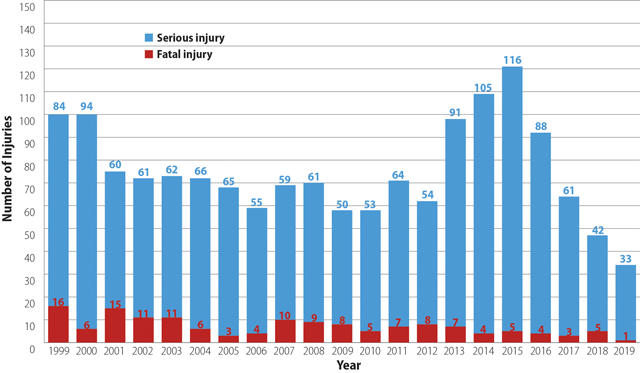

From 2010-2019, Oslo had an average of five to seven traffic fatalities a year. Some U.S. cities of similar size to Oslo (population 693,491 in 2018) have more than double the traffic fatalities in a given year. There are no records of children between 6 and 15 years old dying in traffic since digital records began in 1999, write Anders Hartmann and Sarah Abel.

The risk of fatal or serious road traffic injuries, on a trip-by-trip basis, has fallen 47 per cent for cyclists, 41 per cent for pedestrians and 32 per cent for drivers between 2014 and 2018. The average number per 1 million trips for cyclists was reduced from 3.2 to 1.7, pedestrians from 0.7 to 0.4, and car occupants from 1.7 to 1.1. Finally, in 2019, Oslo achieved a critical milestone: no vulnerable road users died all year, and only one car driver died.

So how did the city get here?

In 2015, the political climate and public will in the City of Oslo changed the tone on accepting continued surface transportation fatalities. The mayor, city council and transport division staff all supported a shift in roadway decision-making from car-centric to people-centric. Reductions in serious injuries and fatal crashes around 2015 coincided with several important changes made that year:

- The city government set a goal to reduce car traffic by one third by 2030.

- The authority to designate bus lanes, bike lanes, one-way traffic and closed streets to traffic was transferred from the police to the city government, allowing swift transformation of parking lanes to bike lanes and closure of through streets.

- The city implemented a bicycle strategy, with an aim to increase bicycle mode share to 25 per cent by 2025.

- Oslo announced that it would make the city center car-free by 2019. The project has led to removal of all regular street parking in the city center and closure to all through traffic.

National road safety efforts have helped drive Oslo’s decision-making, especially when it comes to vehicle standards, driver education and enforcement of road rules. Vision Zero was adopted in Norway in 2002, and the country is currently one of the safest for road users in the world. The Norwegian Public Roads Administration published a National Cycling Strategy in 2003, which contributed to improving cycling in Oslo. The National Cycling Strategy has one goal, to make it safer and more attractive to cycle.

In 2015, Oslo announced its own bicycle strategy, aiming to increase the modal share of cycling from seven per cent (in 2018) to 25 per cent in 2025. In June 2016, the city released The Oslo Standard for Bicycle Facilities, which prioritized safety and modal share for bicycles through rigorous design standards to accommodate safe cycling on all road types. Contraflow cycling has been one of the most widely implemented measures, to allow cyclists to choose the safest possible route. Before 2015, facilitating contraflow cycling was not allowed. Today, contraflow cycling is allowed on most one-way streets in Oslo.

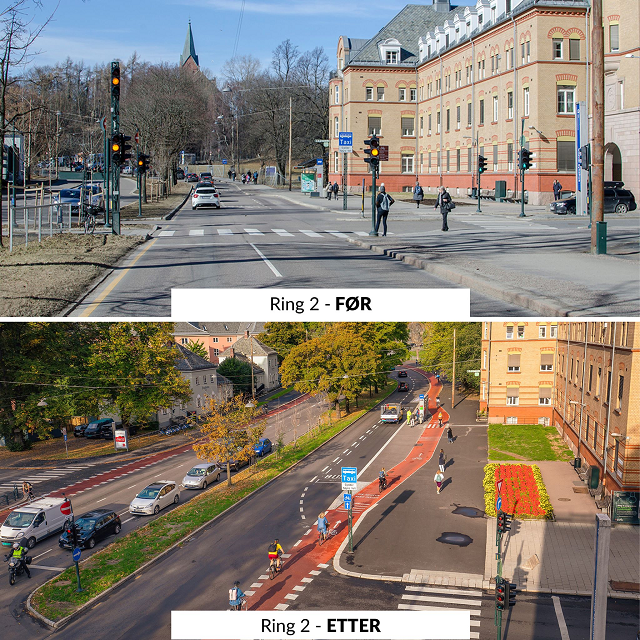

Bike lane implementation has increased ten-fold

Shifts in departmental authority also allowed the City of Oslo to more rapidly implement road design measures. When the Norwegian Public Roads Administration transferred the authority of traffic-controlling signage and markings from the police to local authorities in the five largest cities, Oslo gained the ability to implement key traffic control measures, like bike lanes, in a matter of weeks rather than years. The city installed dedicated bus lanes, restricted traffic on light-rail corridors, and built bicycle lanes in lieu of on-street parking on high mode-split streets and where increased transit and cycling was needed and encouraged. The city has now increased the rate of bike lane implementation 10-fold, from an average of 1.5 kilometer (1 mile) per year, to more than 15 kilometers (9 miles) in 2019.

Owning and managing the vast majority of roadways within city limits has allowed Oslo officials to rapidly evaluate safety and make design decisions, and to set aggressive targets for safety and mobility. While they must still work under national policies and standards, city officials also maintain their own road and cycling design standards, and the city has recently increased standard sidewalk width from 2.5 to 3 meters (8 to 10 feet) to accommodate increasing pedestrian traffic.

In all design changes, the city has prioritized safety for vulnerable road users, particularly pedestrians. When it began closing streets to car traffic, some at peak pedestrian and cycling times and some permanently, the city targeted areas with high pedestrian and bicycle crashes. At intersections across the city, pedestrian visibility has been improved – by installing bump outs, for example, where parked cars or turning lanes obstruct sight lines. Oslo also requires high-visibility, ladder-style crosswalks at all pedestrian crossings.

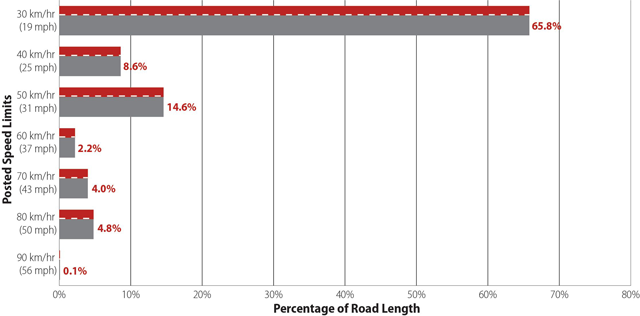

The City of Oslo also implemented targeted safety measures in areas where pedestrians and cyclists are most vulnerable. Officials limited speeds around schools to 30 km/hr, installed speed humps and reduced pedestrian crossing distances to 8 meters. In high-density, mixed-use areas where closing streets to cars was not an option, the city considered one-way streets to limit traffic and used various roadway interventions such as narrowed lanes with vertical elements, tight curb radii requiring drivers to turn more slowly, separated bicycle infrastructure wherever possible, and wide sidewalks. In these more complex street environments, design changes force drivers to pay attention, drive slower and be cautious of pedestrians and cyclists.

Design changes force drivers to pay attention

While Oslo has the authority to set speed limits as it sees fit, it prioritizes control of vehicle speeds by physical measures rather than enforcement. In most cases, the city combines revision of speed limits with measures such as speed humps, tighter curb radii and bump outs, to ensure that drivers adhere to the new speeds. Arterials are typically posted at 50 km/hr, smaller streets with bus traffic at 40 km/hr and local streets at 30 km/hr.

One important factor in reducing roadway fatalities has been limiting Oslo’s streets to one lane for cars in each direction. On streets that once had three or four lanes, the city has installed bus lanes or bike lanes instead. Not only does this limit traffic, it makes the act of crossing the street less complex. With only one lane for cars, pedestrians have an easier time focusing their attention, and vehicles are less likely to obscure people crossing.

Since 2015, Oslo has implemented 50 kilometers of bike lanes, removed parking spaces equivalent to 4,250 cars from its streets, installed around 500 speed humps, and lowered speed limits so that almost two-thirds of the road network now has a speed limit of 30 km/hr. The city government has vowed to make 30 km/hr the standard citywide speed limit in the future.

Oslo set a goal in 2015 to reduce car traffic by one third by 2030. To reach this goal, the city has implemented a congestion charge, installed 52 new road toll gates and increased the tolls, which finance a large part of the city’s investments and operations in walking, cycling, public transit and road safety. Data indicate traffic has started falling, enabling more bus lanes, bike lanes and speed humps to be installed.

We must all strive to achieve the same goal

Using road crash data to improve safety has been equally critical to Oslo’s Vision Zero success. Every fatal crash is investigated by the Norwegian Public Roads Administration, with input from the police, to look at factors that contributed to the crash and its severity. Such investigation reports regularly include recommendations for road improvements, both at the crash site and to prevent similar crashes elsewhere. In 2018, for example, a fatal cyclist crash led to the redesign of four bus stops, four intersections, and widened bike lanes over a distance of 1 kilometer that included signal timing and separated junctions for cyclists at similar intersections to where the fatal crash occurred. These reports also give transportation professionals an understanding of crash causation, a critical concept of the Safe System approach to road safety.

Now that transportation professionals know it is possible to achieve zero and can learn from cities like Oslo and Helsinki, we must all strive to achieve the same goal. We have an obligation to protect all road users, especially vulnerable road users. With a common goal of zero, political priorities and aggressive standards, we can ensure that pedestrian and bicyclists are no longer vulnerable in our cities. We must start now – as Oslo has been prioritizing safety of pedestrians and bicyclists for decades – and decide that even single-digit fatalities are not acceptable. Transportation professionals should take these lessons and apply them all over the world so no motorist, pedestrian or bicyclist need risk their life just to get from point A to point B.

Anders Hartmann is an urban planner based in Oslo, Norway.

Sarah Abel is the Transportation Planning Director at ITE.

This article has been republished courtesy of TheCityFix.com

It was first published in the May issue of ITE Journal © ITE, all rights reserved.