Vertical housing environments for children, youth and families

During the Antwerp seminar on Children in the Sustainable City, a round table on children living in high rise buildings was organized. Why high-rise as a theme in a seminar on sustainable futures? Cities all over the world consider high-rise/high density environments as one of the solutions to build sustainable cities.

We could, of course, discussed whether we like or dislike that as an option, but that was not the aim of the round table. Building in increasingly higher densities will be the future whether we are in favour of it or not. That is why the central question of this round table was: HOW can we connect childfriendliness with high rise housing?

Part one

As the facilitator of the round table, I started things off with my personal statements. Thereafter three short presentations which were followed by a discussion.

In the introduction, I stated that I have already been fascinated by questions concerning childfriendly high rise for some years. That all started with my research in Hong Kong about how families ‘survived’ in high rise apartments (Karsten, 2015). Hong Kong is the high rise city of the world. My study revealed that Hong Kong families considered their vertical living as a matter of course. It became clear that the western negative discourse on family life in flats is not generally applicable, but a culturally specific construction.

To illustrate this point: just one result from my research. I asked the Hong Kong families: Have you ever dreamed of a single family home? Most families answered: “What do you mean?”. And then after a short explanation from my side – to my surprise – they started to sum up all the disadvantages of a living at the ground level: too much work, not hygienic, lack of privacy and so on. They preferred high rise apartment living. The single family home is not the ideal the Hong Kong families were dreaming of! This doesn’t say, however, that there was no critic on the high rise they were living in. In order to group their critics (and of course the possible answers), I made a distinction between three different geographical scale levels: apartment, building and neighbourhood/city. Each of these levels got attention during the discussions in Antwerp.

To read Karsten (2005) in full click here.

Part two

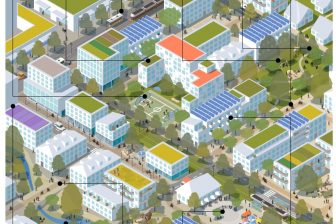

After my introduction, each of the three speakers of the round table on high rise presented their work. The first speaker was Wouter Vanderstede, an urban planner and anthropologist working at a Belgian Ngo: Kind en Samenleving (Childhood and Society Research Centre). He focused on some fundamental planning & design principles for child friendly high-rise buildings, based on a specific high-rise building in Leuven and an analysis of sustainable housing projects in Europe.

Key issues in his presentation were among others the necessity of building a network of child provisions, following an appropriate scale, providing flats with an own identity and buffering a public-private continuum. Secondly, Marlies Mareel, Jo Boonen and Sven De Visscher from the University College Ghent presented their study on high rise with building blocks of spatial quality, which form a framework useable for social and spatial professionals active in vertical housing environments. The building blocks are a set of guidelines derived from a literature study which have been contextualized and tested through participatory research with children and teenagers in four different vertical housing neighbourhoods in Belgium.

The last speaker came all the way from Australia: Natalia Krysiak. Nathalia is an architect from Sydney who investigated best practices for childfriendly neigbourhoods in notably high rise environments like Singapore, Tokyo and Hong Kong. She gave lots of interesting examples of how to accommodate a family in high rise and also some negative examples. Among the positive ones, she gave an illustration of the inter-generational approach in Singapore with facilities for three generations in the inner court of high rise estates. With the building of both children’s and elderly people facilities, it turned out that the older generation was less inclined to complain about the noise children make when playing in the communal gardens.

The lively discussion afterwards brought forward that high-rise is not something perse negative for children and youngsters. However, both the needs of children and their families need specific attention. On the geographical scale level of the apartment, it was suggested that more storage capacity is needed to house families. The building should accommodate social connections between family households by building in spaces to be used for children/families like child care facilities, supermarket or a library. These in-built facilities should also be welcoming to the neighbourhood. Most importantly the different in-between spaces should get extra attention. How to relate spatially and socially the apartment with the other apartments on the same floor? And how to connect the housing estate with the neighbourhood? It was concluded that not all questions could be answered and that we are in need of more research on family and high rise.