Why Does Universal Street Design Matter?

Accessibility remains a challenge for Belo Horizonte’s bus rapid transit corridor. Improving public transit requires a hard look not just at vehicles and routes but at how people get on and off them.

Too often, design that takes into account how all different kinds of people might use a system is not standard in urban planning.

In Brazil, almost 25 percent of the population is physically disabled. Brazil’s population is also aging – it has the fifth oldest population in the world. By 2030, there will be more elderly people than children. While Brazilian cities are transport pioneers in some respects, accessible design for the less able remains a challenge.

Take Belo Horizonte, for example. The city of 5 million has an advanced bus rapid transit (BRT) system and the highest quality of life in Latin America, according to the United Nations. But a closer look at some design decisions shows serious safety problems made worse by an aging population.

In 2016, Belo Horizonte produced an accessibility assessment of its BRT stations and surroundings. The assessment covered sidewalks, curb ramps, pedestrian crossings, pedestrian bridges and platform elements. It found, among other things, clear accessibility problems for stations that are forcing riders into dangerous behavior patterns.

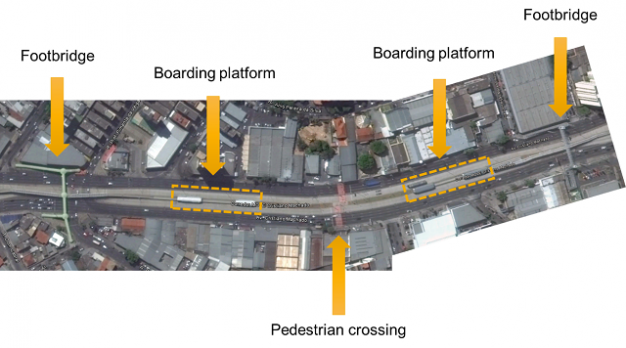

The map below shows a station in the BRT corridor. It shows one station with two boarding platforms, one for city services and another for regional services. The access points for both platforms are adjacent pedestrian bridges, and there is a pedestrian crossing with a traffic light between the two.

Let’s say a pedestrian in the figure below wants to access platform “X” of the station. It seems like the best and most direct option is to cross the street on ground level at the light and get to the station.

But, in fact, the boarding platforms do not have doors on the sides facing the pedestrian crossing, and there’s no path through the medium to the platforms, either.

Instead, pedestrians are meant to use the footbridges and ramps above the flow of traffic to get to the other side of the platforms.

These design decisions have had several consequences.

First, many people still try to use the more direct route of crossing at ground level and approaching the stations from the green medium. As they approach the boarding platforms, they are forced into the BRT expressway itself in order to climb up to the platform or have to turn around and complete an even longer course correction.

Second, the longer, safer route is especially onerous for the elderly and disabled, who have to navigate two elevation changes. What is simply annoying to navigate for the able bodied is a real barrier to entry for others.

Belo Horizonte is developing plans to improve accessibility at its BRT stations, thanks to this assessment. This is a complex urban planning issue, and to address it and improve their mobility systems, cities need constant evaluation and adjustments.

But accessibility planning remains an afterthought in too many public transport systems.

In many cases, the lack of disabled or elderly persons using public transit is not because they do not exist or want to use these systems, but because they simply cannot.

It’s important for cities to minimize obstacles to mobility, prioritizing the movement of people, rather than particular modes or vehicles, and keeping in mind the diversity of the human form. Belo Horizonte shows that closer attention can not only benefit the elderly and disabled but all users.

Feature photo by Mariana Gil/WRI Brasil. Other photos: Marcelo Araújo/WRI Brasil.

This article was originally published by The City Fix.