A park in Bangkok is helping prevent the city from sinking

The city of Bangkok is sinking one to two centimetres a year. Coastal erosion, rising sea leaves and rapid urbanisation have created the perfect storm. Landscape architect Kotchakorn Voraakhom has designed Chulalongkorn Centennial Park to help fortify the city against climate change.

The park also provides a haven for children. “Kids love to play in these spaces, where they can engage directly with nature,” says Voraakhom.

Urbanisation

Kotchakorn Voraakhom is the founder of Landprocess, a Bangkok-based design firm that builds public green spaces and green infrastructure, aiming both to increase urban resilience and to protect vulnerable communities from the devastating effects of climate change. She’s also the founder and CEO of Porous City Network, a landscape architecture social enterprise working to increase urban resilience in Southeast Asian cities, where flooding and water scarcity are exacerbated by dense urban settings.

Bangkok used to be considered the Venice of the East as a series of canals connected the city. Over time these canals were have been replaced with slabs of grey. Reflecting on her childhood experiences Kotchakorn Voraakhom explained: “When I was young, there were rice fields and canals in the city. I could hear boats from my house in central Bangkok. Now, all those fields and canals have been stopped with concrete and covered by highrises. All of the buildings and concrete become obstacles for water to drain, so the city floods.”

Chulalongkorn Centenary Park

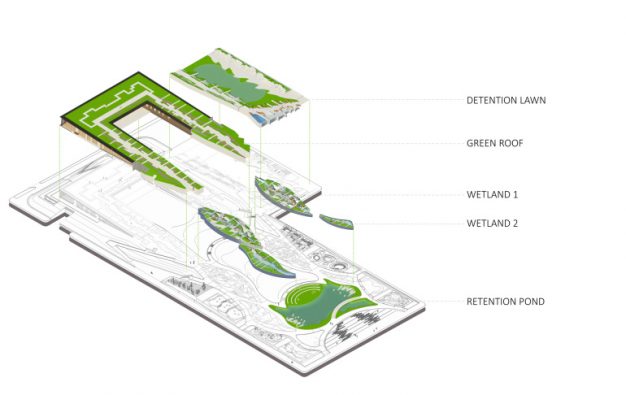

Chulalongkorn Centenary Park commonly referred to as ‘CU Park’ is built on eleven acres of land at Chulalongkorn University. The park is designed to retain and redirect floodwater that would otherwise flow into city streets. As well as help to reduce the urban heat island.

The park can hold up to a million gallons of water. One side of the park is built at an incline that helps funnel water into a giant container. While a raised green roof directs runoff water through sloped rain gardens with native plants. Other sections of the park include an herb garden, trails, and a recreation area.

Voraakhom explained, “with the retention pond and lawns, we can hold the flood water as long as we want if the entire city is flooded. Then, eventually, we can drain the park into the public sewage system when all the other flooding in the city has been drained.” The inspiration for this came from Thailand’s ninth monarch King Bhumibol monkey’s cheeks metaphor. A monkey will store food in its mouth until it is needed in the same way King Bhumibol felt Bangkok should hold flood water until the city needs it.