Children and the city: how industrialisation shaped modern childhood – Pt 2

In this second part of a two-part essay, the Greek writer and academic Eleni Kapa-Karasavidou describes how the plight of children living – and dying – in the new squalor of the industrial age changed popular perceptions of the romantic child into something more ambiguous, leaving the emerging modern society’s construct of childhood muddled and confused.

(read the first part of this essay here)

It was the Romantics, breaking with the abiding Puritan discourse – and also ‘in rebellion against the coming of mass society, seeing in childhood the glimpses of a lost paradise’ (Cox, 1996, pp.80-21) – who first took the image of ‘the child’ and equated it to the embodiment of ‘innocence’.

This conflation – of the construed nature of children, with the tremendous, abstract notion of ‘innocence’ – not only smelted the concept of ‘the child’ into a kind of ‘super ego’ (if we are allowed to borrow this useful psychoanalytical term) that put on trial the collective social conscience of the time (contributing to a massive cultural shock!), but also imbued this new archetype with a wealth of mystical, neo-sacred significance. ‘Child is the Father of the Man, the Eye among the Blinds’ said Wordsworth, the pre-eminent poet of the Romantic era.

‘With the main stream of emerging bourgeoisie seeping in their consciousness, allaying and fretful, came a notion which was not new (in some senses was as old as Christianity itself) which imbued the child with mysticism and with power’ (Cox, 1996). In this way ‘the child’, with its particular and opposing qualities to those of the adult world, acquired a huge symbolic power, creating not only big social changes but also what we might now call a ‘moral panic’. Society both revered this new, mythical child and at the same time became anxious about its implications for the social hierarchies of a barbarous yet complacent system. The archetype of the innocent child image was a powerful agent in this social awakening, and became deeply embedded within folk myths and, thus, within the heart of the culture itself.

Dickens shocks the middle class

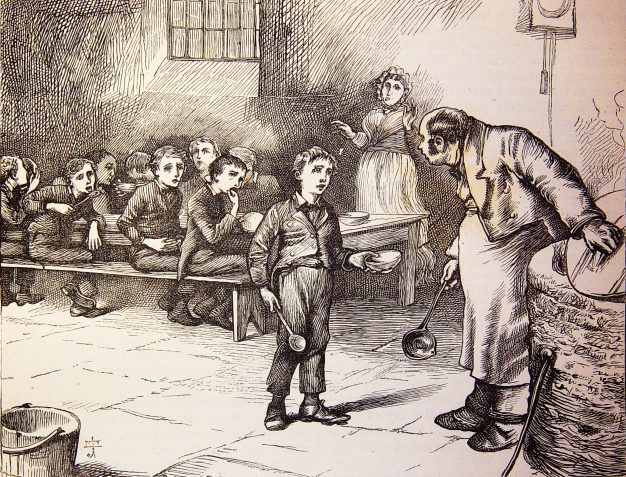

In stark contrast with the, by then, orthodox image of the ‘romantic child’, Dickens’ depiction of the plight of poor children – including, most disquietingly, the extent and manner of their deaths (Somerville, 1982, p.170) – shocked the masses, especially of the English middle class, throughout the Victorian era. If the popular myth of the dark ages – that ‘it was enough to make love to a young virgin in order to cure oneself’ – still carried some meaning it was perhaps in the subconscious knowledge that, ultimately, there was no healing.

The invention of new technologies, ushering in the ‘age of the machine’, was considered by some as a manifestation of God’s wisdom and the solution to humanity’s problems. This new Utopia soon collapsed however, amidst the heavy smog swirling around the grime and squalor that appeared wherever the factories using this new technology were built. It was a Utopia soon to be replaced by another idealized vision, wherein ‘Proletarians will solve the dispositions and social wrongdoings of the age’.

From within the factory slums, breathing their smoke-filled air, a certain figure appeared, gazing directly, accusingly, into the eyes of adult society. This was the ‘child of the poor’, an outcast of the new era. It was the Victorians’ guilt (Somerville, 1982, p.172) and fear for this victim of their progress, who possessed, from the inherited Romantic discourse, an image of beauty and fragility, as well as a freedom from social conventions (Cunningham, 1991) that, along with the bourgeois-oriented agenda to homogenise childhood, imbued the child of the poor with ‘a sheer power’ (Mavor, 1994 p.188) and ‘energy in the end of the century’. (Cox, 1996). This was the power of ‘forgotten’ nature, left behind in this era of factories, but still manifest in the child. In this way, the image of the child living in dire poverty came to represent a confused and ambiguous morality in the popular mind (Cox, 1996, p.152).

A virtuous enemy

The innocence of the child within ‘the ideal of the bourgeois home’ (Auerbach, 1982) became on the one hand the foundation and ultimate justification of the social hierarchy and, on the other, a virtuous enemy of modernity (Cox, 1996), embodying violated nature itself (Somerville, 1982), which sooner or later was going to have its revenge.

Today, as the world undergoes yet another series of blistering changes in social, cultural and financial structures, once more our cities are the main ‘stage’ for a new era of fear and hope. Our very notion of Identity again goes through some fundamental changes, creating the need to redefine ourselves and others. Once more, children – along with women – are the primary victims of change, and their image is seconded, alternately, to raise our awareness and ease our collective conscience. Perhaps, this time, it can be different? It is up to us.

Eleni Karasavvidou

Image: F. Barnard (1875), from The adventures of Oliver Twist by Charles Dickens, London: Chapman and Hall.

References

Auerbach, N., 1982, Woman and the Demon: The Life of a Victorian Myth, Cambridge, Harvard University Press.

Cox, R.,1996, Shaping Childhood, Themes of uncertainty in the history of adult-child relations, London, Routledge.

Cunningham, H. ,1991, The Children of the Poor: Representations of Childhood Since the Seventeenth Century, Oxford, Blackwell.

Hall. P. 1982, Cities of Tomorrow, London Rutledge.

Sommerville, C.J. ,1982, The Rise and Fall of Childhood, Beverly Hills, Sage.