An urban planners guide to engaging with children

Children are the group in society, arguably, most sensitive to their surroundings and most affected by changes in their local environment. The UN Convention on the Rights of the Child enshrines in international law a commitment to listen to the views of the child, and to uphold their need to play and participate in public life. Despite this, the planning sector in the UK (and abroad) has struggled to incorporate the child’s perspective into its decision-making.

Far from being a burden to planners, thinking about children can enhance both the participation process and the quality of decisions made. Indeed, a child-friendly city is more likely to be a person-friendly city, encapsulating many of the standards that planners strive for. However, some of the greatest barriers to adults thinking critically about children are societal assumptions about what they are like, what they do, and what they can and cannot understand. Having worked with and studied children in the 8-12 age group, I reflect here on some of the questions planners who wish to take a more child-friendly approach to their work can ask themselves.

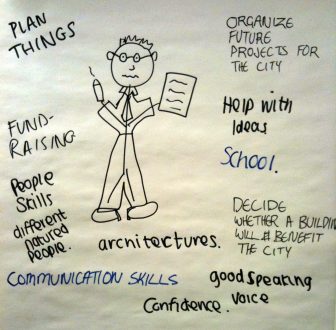

Teenagers draw their ideas of ‘the typical planner’

What can you already find out?

A plethora of studies show how children use and perceive space (click here for example). This is about more than just playgrounds, as children have wider requirements for independence and will often prefer less structured play opportunities. Not all this information is necessarily easy for planners to access, but children’s organisations and advocates can use the research to share insights and point planners in the right direction. Understanding these basics allows direct participation with children to focus on the contextual issues, rather than starting from a point of no knowledge.

How much do children need to know about planning before they can participate?

Planners may assume children are too naïve to be meaningfully involved in the planning process. However, what does any community member (adult or child) ever need to know before they can comment on their own experience? Instead of expecting children to come out with fully-fledged ideas and understand how they can be implemented, if we recognise that their insights are independent of planning know-how, then talking to them becomes easier.

How can you access a child’s knowledge?

Children are experts in their own everyday lives, and are able to express themselves in a number of ways. Starting with simple questions like ‘what do you like/dislike about your area?’ is all you need to begin a conversation about place with children. Methods such as drawing, annotating maps, or going on walks can enhance the level of insight you receive, but being open to dialogue on their terms is the first (and most important) step to their engagement.

How can you manage children’s expectations?

Adults aiming to engage children may be worried about the expectations that this gives rise to, or about how practical their ideas might be. This can be particularly true for planning when the time-scales of development and complexity of regulations, procedures and competing views are difficult to balance and communicate. However, these issues are often difficult for all types of people to fully comprehend. Perhaps the best solution, therefore, is to be honest with children and let them know what is likely to happen, and where their views and ideas can make a difference (even if not immediately). This is a challenge that planners will always face, but thinking about how to explain complexity to children can have value for explaining complexity to other types of people too.

Author: Jenny Wood

Photo Credit: photo by Nick Wright (teenagers draw their ideas of ‘the typical planner’) & Nancy Regan (https://www.flickr.com/photos/nancydregan/)