Protecting children from exploitation means rethinking how we approach online behaviour

Raising children in the digital age is increasingly challenging. Many younger people are relying more on screens for social interactions. They experiment with new media sharing options, such as TikTok, Snapchat and BeReal, but without necessarily having the ability to consider long-term consequences.

This is normal, as children still have an underdeveloped prefrontal cortex: the part of the brain that is responsible for reasoning, decision-making and impulse control.

Parents, who are tasked with anticipating the consequences of digital interactions, are overwhelmed. Many parents might lack the digital literacy to guide their children through the numerous social media options, messaging apps and other online platforms available today.

This situation can lead to children falling victim to online sexual exploitation. In our research, we collected data from a diverse group of experts in the U.S. and U.K. This included interviews with internet safety non-profits, safeguarding teams, cybercrime police officers, digital forensics staff and directors of intelligence. A main cause behind the rapid escalation of online child sexual exploitation is the ability to share explicit content online.

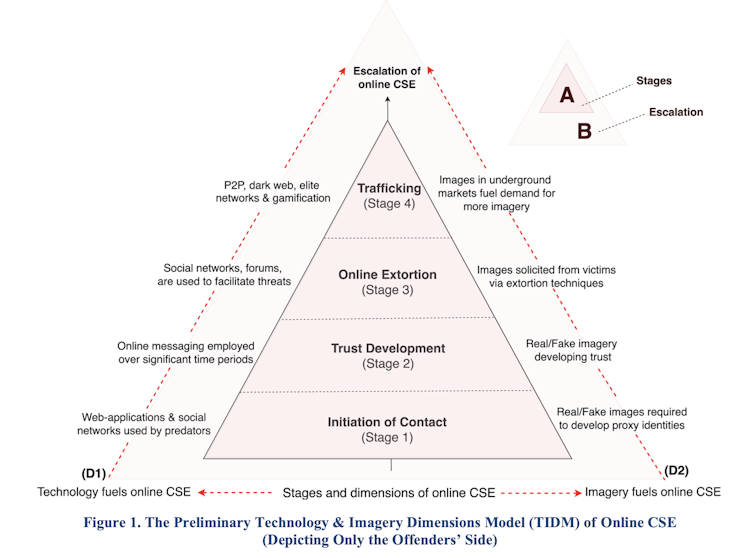

Our research unveiled four distinct stages used by perpetrators.

Perpetrators and escalation

A figure showing how child sexual exploitation takes place online.

A figure showing how child sexual exploitation takes place online.

Author provided

In Stage 1, perpetrators utilize various technological tools and networks, such as social media, messaging apps, games and online forums, to initiate contact with potential victims. They often create false identities by using fake images to develop convincing digital personas, through which they approach children, such as pretending to be a “new kid on the block” seeking new friends.

In Stage 2, perpetrators use tactics like posing as a similar-aged child to build trust with potential victims. This can happen over a considerable period of time. In one case we studied, a 12-year-old in Lee County, N.C., received 1,200 messages from the same perpetrator over 2 years. During this stage, offenders may send their own explicit images to lower a victim’s suspicion, and may target multiple victims until successful.

In Stage 3, perpetrators engage in online extortion. They use photographs provided by victims or manipulate innocent photos to appear sexual or pornographic. Perpetrators then share these images to their victims to keep them in a state of suspended humiliation. This is further escalated when perpetrators threaten to share these embarrassing images with the victim’s friends, teachers or family unless their victims send more explicit photos or videos.

Many extortion techniques and direct threats are being used at this stage. It is difficult to imagine the psychological pressures this can create for children. In one case described to us, a 12-year-old girl uploaded 660 sexually explicit images of herself to a cloud-based storage account controlled by a 25-year-old perpetrator before seeking help.

In Stage 4, perpetrators start trafficking these images on peer-to-peer networks, the dark web and even child pornographic networks.

A video outlining how child sexual exploitation can take place online.

Preventing online exploitation

There are common mistakes that parents can avoid to help prevent exploitation. By sharing these, it is our hope that parents, policymakers, school boards and even children will rethink their approach to online behaviour.

1. “That won’t happen to us!”

Many victims and their families fall prey to optimism bias, thinking that negative events are unlikely to happen to them. However, online crimes can affect anyone. Unfortunately, these incidents occur more frequently than most people realize. No family is exempt from the potential dangers of the online world.

2. “Everyone else is doing it!”

Parents oversharing pictures of their children online has become commonplace. Many cannot resist the pressure or temptation to post photos of their children on social media. Very often, it is these photographs that are edited and distorted to appear as pornographic. All family members need to resist the pressure to overshare pictures online.

3. “My kids don’t mind!”

Many children today have a digital presence that was initiated and maintained by their parents without their consent. This disregard for children’s privacy not only undermines their autonomy, but can also have a lasting impact on their self-confidence, their personal and professional future, and the parent-child relationship.

Creating a digital life for children at a young age could also desensitize them to the importance of online privacy. The assumption that children will not mind is erroneous. In one case, a court in Rome decided that a mother should take down all images of her son from Facebook and pay a €10,000 fine if she continued to post photos without his consent.

4. “We cannot keep up with their technology!”

Many parents are overwhelmed and intimidated when they cannot keep up with their kids. As technology continues to play a critical role in children’s lives, improving digital literacy of parents through online resources and schools needs to become a priority. Parents need to seek and receive support to understand the technology their children are using.

5. “They’re just online, talking to friends!”

Despite being very involved and interested in who their children talk to on the way home from school or at their friends’ houses, parents might not be as aware of who their children talk to online. Just like they show an interest in their child’s real-world interactions, the benefits and dangers of online behaviour need to be an equally important and frequent topic of conversation.

Online child sexual exploitation is a grave and multifaceted issue that demands our unwavering attention. Only by carefully considering these critical concerns can we hope to prevent children from falling victim to these crimes.![]()

By Jan Kietzmann, Professor, Gustavson School of Business, University of Victoria and Dionysios Demetis, Senior Lecturer in Management Systems, University of Hull

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.