Learning pods are now helping vulnerable students. Will the trend survive the pandemic?

Like many New York City charter schools, Brooklyn’s Ascend network started off the year fully remote. But just a few months in, it became clear: Remote learning wasn’t working for certain students.

Attendance dipped, and teachers struggled to reach students at the network’s K-12 schools. Many of the children come from some of the poorest neighbourhoods in Central Brooklyn, and some live in vulnerable housing situations. They needed a safe, supervised place for effective virtual schooling.

By Lauren Constanino and Jacqueline Neber, THE CITY

“We have students in transitional home situations, and we have students who really needed an optimal learning space,” said Ania-Lisa Etienne, a teacher at Brownsville Ascend Middle School, one of the charter’s 15 schools.

School leaders heard the feedback from teachers like Etienne, and by November decided to change tracks.

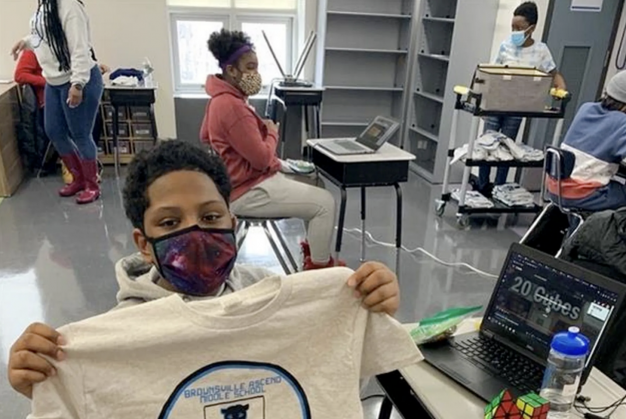

They transformed some of their Brownsville classrooms into learning pods — making space on campus for small groups of students to attend virtual school with the help of a learning proctor or “pod leader” who supported them throughout the school day.

Some teachers volunteered to be pod leaders. Others were led by furloughed school food service workers, as well as paraprofessionals, who were hired and trained by an outside agency. Roughly 380 of the network’s 5,000 students had enrolled in 15 learning pods across its Brooklyn campuses, as of March.

“We just need kids to be in class,” said Rachael Sheridan, another Brownsville Ascend Middle School teacher. “If they’re not in class, we can’t even do the work we’re trying to do.”

Pods price out many

From the start, learning pods raised questions around equity. Small private pods, many gathering in homes, began popping up across the country, with some as pricey as $13,000 per semester.

These kinds of pods often excluded lower-income families, and didn’t always feel inclusive to families of children with disabilities who might need special support. Many education observers worried that these self-created groups would widen already existing educational disparities in a year defined by disrupted, and often, less instructional time for most children.

But the pod concept has expanded beyond the home. In an effort to even the playing field, some schools, churches and community-based organisations have been offering students of all income levels this kind of in-person, small-group option. Many experts say the pod model — with the individualised attention it provides — can be helpful to the most vulnerable students.

“It is not a traditional classroom, and the environment is different, and allows out-of-the-box thinking,” said Lori Podvesker, director of disability and education policy of INCLUDEnyc, an advocacy group that offers free training and resources to young people with disabilities and their families. “Maybe they’ll let a kid chew gum, which helps with their sensory issues. Maybe they’ll let them stand up.”

In New York City, however, pods remain largely the domain of privileged families. The helpline run by INCLUDEnyc — which fields 3,000 calls each year from parents — did not receive a single inquiry about learning pods since the beginning of the pandemic, according to the organisation.

“There are many other structural barriers, many other needs that are pressing before getting to this,” Podvesker said.

Making pods more accessible

A handful of groups like are looking for ways to make pods more equitable, such as the Center on Reinventing Public Education, which is tracking and researching pods run by schools or community organizations across the country.

The Seattle-based group, which has received funding from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, says it sees “public education as a goal, not as a set of fixed institutions.” (The Bill & Melinda Gate Foundation is also a Chalkbeat funder.)

According to a database assembled by the organisation, there are at least 330 district and community-supported learning pods, based on national media searches and referrals. The database has identified 14 pods in New York State, six of which are in New York City — including the citywide Learning Bridges child care program, run by the Department of Education.

Though the data is limited by publicly available information, it offers a snapshot of how learning pods are becoming more popular among school districts and in non-school spaces such as churches, recreation centres and non-profit organisations across the country.

Keri Rodrigues, the founding president of the National Parents Union (NPU), is trying to solve for inequities by funding grassroots pod efforts across the country. Her organisation has given almost $1 million in grants to parents and community centres who wanted to start their own learning pods during the pandemic. The grants prioritised low-income people of colour, whom Rodrigues describes as “the people who are closest to the pain that never have resources.”

Before the grant program, NPU provided resources to families who needed support while working with their children from home through YouTube videos and its website. After the learning pod grant fund was announced, NPU received more than 500 applications from parents from across the country, requesting different sums of money to address issues children were facing during remote learning.

Several of the pod grant applicants asked for sensory equipment like weighted blankets and fidget items that aim to help students with learning differences. Rodrigues’ son, who has autism and ADHD, is in a paraprofessional-run pod in Somerville, Mass. with three other students with disabilities. He is thriving in that environment, she said.

“Pods are far more culturally competent and inclusive and responsive to the needs of the community,” said Rodrigues. The key is providing the resources and funding so that families and community-based organisations can continue this new approach to supporting vulnerable students, she added.

For Ascend, the model appears to be paying off.

Pandemic solution to pandemic problem

Depending on the size of the classroom, the pods at Ascend have anywhere from two to 15 students sitting six feet apart.

There are also robust safety measures in place, including mandatory mask-wearing, hand sanitising stations, enhanced cleaning procedures and signage placed around the building to remind students and staff where to stand, according to Brandon Sorlie, Ascend’s chief academic officer. (The network was fully remote except for the pods because the overwhelming majority of students did not want to return to school buildings, Sorlie said.)

After the pods opened, Ascend officials reached out to the network’s “most vulnerable students,” starting with those experiencing housing insecurity, Sorlie said. Then teachers were asked to target students who weren’t showing up to class or whose work completion rates were low. Other groups that enrolled in the pods include students with disabilities and English language learners.

Courtesy of Ascend Public Charter Schools. Arielle Pope is a student at the East Flatbush Ascend Charter School.

One of the students Ascend reached out to was eight-grader, Anastasia Clay, who was struggling with attendance due to technology and connectivity issues at home.

“It prevented her from getting the curriculum, handing in assignments on time, and getting her attendance taken properly,” said her mother, De-juana Rollins. “The school reached out and said ‘Hey, listen, Anastasia is not doing well with remote, we need to get her in here.’”

Anastasia, who has an Individualized Education Program, said the learning centers were a better environment to help her complete assignments.

“My room has a lot of things that distract me when I’m trying to do my work,” she said. “It’s more of a professional environment for me to be able to do my school work in.”

At Ascend’s pods, learning proctors are encouraged to communicate with parents and teachers to support the student throughout the day. Rollins appreciates this one-on-one contact and how quickly school reaches out if there are issues in the classroom or with missing work.

“I’m a single parent, I have a lot going on,” Rollins said. “There’s a lot of times where I feel bad because I get things late, but here they’re making me aware. I like that kind of instant communication, it’s gratifying for me.”

Ascend teacher Etienne signed up to become a pod leader. She recalled how the setup helped one student who was failing to show up to her classes.

The moments in-between classes provided an opportunity for Etienne to connect with the student by checking-in with her when needed. That relationship-building, she believes, made a difference in bolstering the student’s improved attendance and participation.

“We have a lot of conversations outside of class about books that she’s reading. She also has incredible taste in music. She is an old soul. ” Etienne said. “Being able to engage in that way and also talk to students her own age. All of that has really helped.”

Boosting ‘joy and morale’

On the other side of the country, children with disabilities in Oakland’s Unified School District (OUSD) in California were experiencing similar problems with remote learning.

Jenn Blake, the executive director of OUSD’s special education department, said many children with disabilities were “struggling communicatively or emotionally and needed access to in-person connections,” and working parents couldn’t provide the direct support their kids needed during the day.

The district decided to launch a pod structure at the beginning of the school year and small groups of students were welcomed back to campuses.

‘We saw the largest benefit in students reporting being excited to attend and happy to see friends.’

Oakland used several metrics to track the success of their learning pods, including student data collected by behavioural technicians and speech pathologists to see whether kids improved over time. The special education department solicited feedback from students and families directly, all while tracking attendance.

“Overall, we saw that the pods did result in improvement in students’ attention to tasks, and we recorded some improvement in social skills,” Blake said. “However, we saw the largest benefit in students reporting being excited to attend and happy to see friends.”

Similarly, Ascend in Brooklyn measured the success of its learning pods through attendance and student participation.

Sorlie said he has seen work completion rates and student engagement improved for groups struggling at the beginning of the school year. But, one of the most notable improvements, he added, was morale among staff and students.

“It’s hard to describe, the almost immediate improvement in joy and morale just seeing kids and families in the building again…it’s why all of our people do this work, really,” Sorlie said.

Post-pandemic pods?

Some school experts believe the learning pod model can be carried over after the pandemic to help students who aren’t benefiting from traditional models of classroom instruction.

“There’s a practical need here that the learning [pods] are solving and that’s why most of the big cities are standing up some of these efforts,” said Robin Lake, director of the Center on Reinventing Public Education, which is researching pods.

Some of those big cities include the Cleveland Metropolitan School District and Marin County in Northern California which have teamed with community-based organizations to create free learning pods for vulnerable students, Lake said.

Many families may not be comfortable sending their children back full-time into large school buildings, and that pods can continue to supplement virtual learning in smaller, more controlled spaces, Lake suggested.

“If I were running a school district next year, it would blow my mind to try to figure out how to provide for all of the kids’ needs. Academic, mental health, social-emotional, everything,” Lake said.

At this point of the school year, the majority of schools in New York City are offering students instruction in the school building five days a week, according to an education department spokesperson. Nearly 70 per cent of students, however, remain fully remote.Mayor Bill de Blasio plans to offer in-person as well as remote instruction next year as well.

As school districts across the country continue to re-open in person, Lake believes they should not return to “normal,” but instead use what’s being learned from pods to create learning systems that are more responsive to student needs.

“The name of the game is going to be flexibility and options as we work our way out of this pandemic and rebuild to something better,” she said. “I don’t know how you can do that if you don’t play with the margins of what’s possible.”

This story was originally published on 14 April 2021 by THE CITY. Sign up here to get the latest stories from THE CITY delivered to you each morning. It is part of a collaboration supported by the Solutions Journalism Network, a nonprofit organization dedicated to rigorous and compelling reporting about responses to social problems.

This article is also part of an ongoing collaborative series between Chalkbeat and THE CITY investigating learning differences, special education and other education challenges in city schools.

THE CITY is an independent, nonprofit news outlet dedicated to hard-hitting reporting that serves the people of New York.