Parents with children at home reach breaking point

But in a disturbing new trend parents with jobs are also reporting high levels of distress, write Dr Barbara Broadway, Dr Susan Méndez and Dr Julie Moschion, University of Melbourne.

Having a job was previously a strong predictor of being in good mental health, but employed parents are now about as likely to be distressed as parents who aren’t employed. Especially striking is the increase in high mental distress among employed parents with primary school-aged children. These parents are now more distressed if they are employed, than if they aren’t.

The pandemic has exacerbated already high levels of what is called work-family conflict, or when the demands of work interfere with family demands – caring for children for example.

Parents of dependent children – who account for 36 per cent of the workforce – are reaching breaking point and a significant policy response is now urgently needed.

Significant policy response is now needed

Melbourne Institute’s Taking the Pulse of the Nation survey is tracking 1,200 Australians each week during the pandemic since March to measure any changes in the economic and social wellbeing of the population.

Our research uses the survey data to analyse how the economic downturn and mitigation measures to limit the spread of COVID-19 may be affecting family life and mental health.

The proportion of parents experiencing high levels of mental distress has tripled since the beginning of the pandemic from 8 per cent to 24 per cent. For Australians without children living at home the rate of increase has been much slower, rising from 11 per cent in 2017 to 18 per cent now.

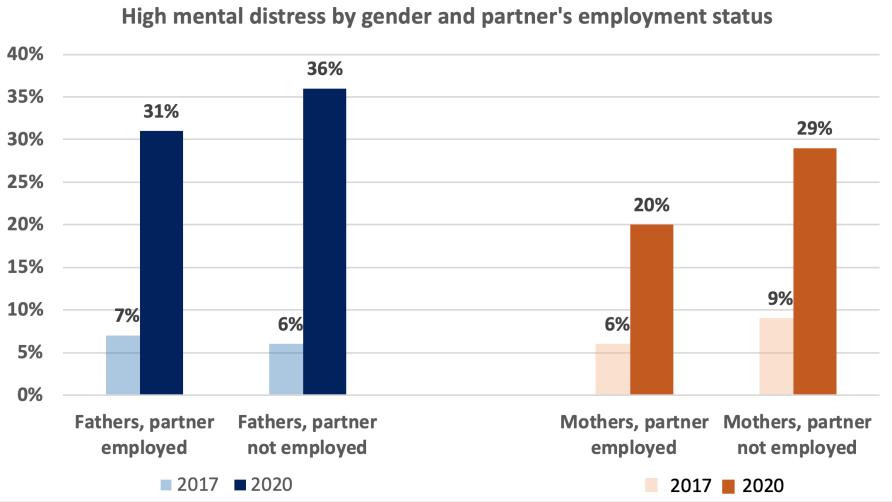

Since the pandemic began, the rise in mental distress has been more severe in fathers than mothers. Fathers with children living in the home experienced a 23 percentage point increase in mental distress compared to an 11 percentage point rise for mothers.

The survey also shows that partner employment is increasingly important to the other parent’s mental health. Again, this is more marked for fathers. Their partner’s employment status made virtually zero difference to fathers’ mental wellbeing pre-pandemic but has become a significant indicator of mental distress now.

The importance of being able to rely on partner income in uncertain times raises important concerns for single parent families who don’t have a second income to rely on. And, according to the latest Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) Survey, the economic stability of single parent families was already in decline before the pandemic.

Sharing the load

The toll of pandemic-related job losses will be felt well into 2021 and the trends we are seeing in mental distress suggest the traditional family model of a sole main breadwinner is no longer sustainable. Many Australians are concerned about their ability to pay for essentials and as trust in job security falters, being in a dual-earner family provides insurance against financial disaster.

The stress we see emerging in families underscores the need to re-design policies to incentivise dual-earner families and encourage mothers into the workforce to better protect the economic security of families, as well as the mental health of parents in times of uncertainty.

Job losses, job insecurity, as well as working from home and home schooling appear to amplify family-work conflict. But, as the data shows, it has played out very differently for mothers and fathers. This is likely because they had made very different choices before the pandemic.

After having children, mothers tended to move to more flexible jobs, working fewer hours and taking on less managerial responsibility, which allowed them to better solve family-work conflicts. When the pandemic hit, fathers had to deal with increased family demands while in jobs that don’t necessarily allow flexible working arrangements – and without the option to change job in the current weak employment market.

Social distancing and lockdown measures also resulted in greater social isolation, breaking down social support systems for families with small children who require a high level of care. Policies aimed at supporting fathers’ involvement in family life can help support healthier families and workplaces.

Wake-up call for policy makers

The current family tax benefit structure actually works against the dual-earner family model by often providing greater financial support to a single-earner-family than a dual-earner-family with the same total income. Harmonising family tax benefits “Part A and Part B” into one payment should be a top policy priority.

There is also a case for greater childcare subsidies targeted at low- and middle income-families. This would increase employment in an expanding childcare sector, and boost the employment prospect for parents (typically mothers) who are locked out of work by prohibitively high childcare costs.

This would be particularly welcome for single parents, who have been giving up formal childcare in the past years. This would also support parents’ mental health given the family would have two incomes to rely on.

The introduction of free kindergarten in Victoria is a step in the right direction and an example for the rest of Australia.

Finally, the toll we are seeing on parents’ mental health should be a wake-up call for business. The negative effects of work-family-conflict on mental distress among fathers demonstrates how important it is for workplaces to make family-friendly policies accessible to men as well as women.

In the absence of response to the sustained mental stress being experienced by many fathers, there will likely be more serious mental health problems in the future.

Another risk of inaction is that mothers will be forced to leave their jobs to alleviate work-family conflict, leading to possibly worse consequences for their own financial security and both parents’ mental health long-term.

A host of flexible workplace policies designed to ease family-work conflict – carer’s leave, flexible access to annual leave, time-off in lieu of overtime payments, part-time work, job share arrangements, and telecommuting – are primarily utilised by women but need to be normalised for men.

We are in dire need of a culture change in the workplace. For such policies to have a tangible effect, it isn’t enough that they exist on paper. It must be genuinely acceptable for men to make use of them.

If the pandemic has proven anything, it is that working from home is, in fact, possible in many workplaces that didn’t offer the option before March 2020.

Government and workplace policy has a central role to play in restoring and resetting the country to a new and better normal post-COVID. A normal that can provide a healthier and more supportive culture for families to thrive while also securing Australia’s economic resilience into the future.

This article was first published on Pursuit at the University of Melbourne. Read the original article.