Being a teacher during COVID-19 – and what the pupils said

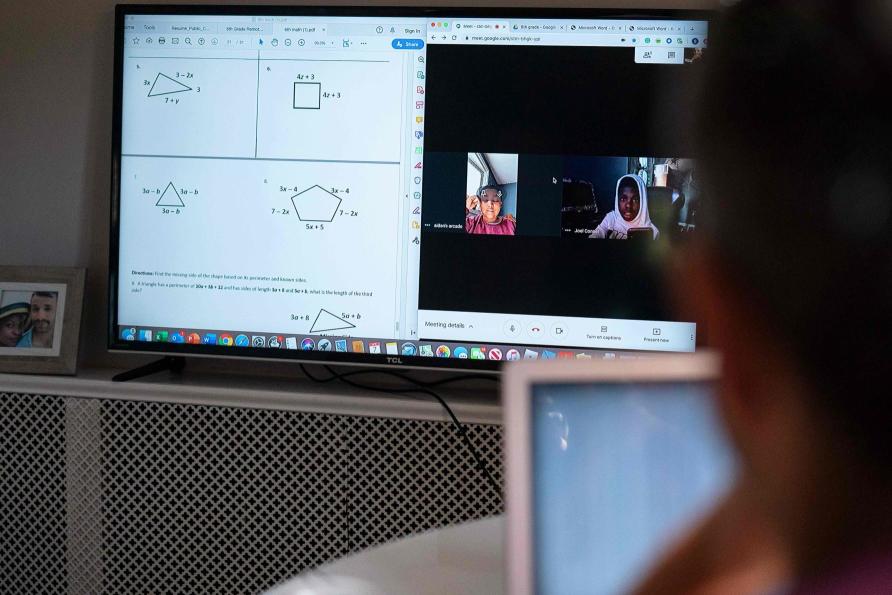

COVID-19 thrust our school communities into a rapid transition to remote learning which affected almost every facet of school-based education.

Understanding the effect on our school students and teachers is crucial as we begin to reconfigure our ideas of what education may look like in a post COVID-19 world.

At the peak of the COVID-19 restrictions, the Melbourne Graduate School of Education conducted a national survey to explore teachers’ experiences in both their digital and physical classrooms which attracted response from almost 1,000 primary and secondary teachers, write Associate Professor Wee Tiong Seah, Catherine Pearn, Dr Daniela Acquaro and Dr Natasha Ziebell.

During COVID-19, teachers working from home juggled the increasing demands of their job; 68 per cent of primary teachers and 75 per cent of secondary teachers report working more hours per week while they moved to remote teaching.

Nearly half of all teachers say they worked almost an entire extra day during this period, and some reported working in excess of 20 hours extra per week.

One teacher says in their survey response: “I’m getting up around 4am most mornings to finalise my day’s lesson planning and to do corrections. That way I’m available during class time for my students and during frees/recess/ lunch. I can then help monitor my three children’s schooling.”

Additionally, almost three-quarters of all school teachers express concerns about the remote learning negatively affecting students’ emotional wellbeing. For many families, this has been a challenging time with teacher, parent and student wellbeing raised as serious concerns.

One teacher says: “The pressure on us right now is enormous. It is difficult to manage healthy breaks away from work because parents and children and our leaders all require so much from us right now… It’s hell right now for teachers. A literal living hell.”

But the teaching experience also presents some new opportunities. Teachers report that they were finding creative, new ways to teach traditional lessons and, for many, the transition is a boost in their digital literacy.

As one teacher notes: “I believe that there will be many opportunities to challenge the many rigid practices of teaching which haven’t changed for years …it is a great opportunity for us to look at education as a whole and ask ourselves, What do we truly value in education? What are we doing well? What can we do better and grow?”

The COVID-19 changes also led to the rapid development of broader professional networks – sharing expertise and working collaboratively.

One teacher says: “I’m planning activities with teachers and discussing online teaching strategies more than I would normally discuss and plan with teachers ordinarily. I’m also sitting in on other teachers’ Zoom lessons or they are sitting in on mine, so I’m witnessing some of my colleagues actually teach for the first time.

“I’m really enjoying learning from their style of teaching.”

The student experience

These survey results also tell that while some students thrived academically during learning at home, for others, it was a very challenging time.

Teachers attribute this to personal factors including things like age, disposition and the capacity for students to self-regulate their learning; accessibility factors, like having a device with reliable internet access and attendance at classes; and environmental factors, which means having a quiet place to work and parental support. The survey looks at the type and use of the technology, as well as the resources available to students.

Teachers reported that 93 per cent of students had access to devices all or most of the time. But some students only used their phone to access classes and for others there were significant access issues. In some households, students needed to share devices with other siblings and/or parents.

The data shows most students had reliable access to the internet while at home, but 11.5 per cent of teachers say that students in their class had stable and reliable internet only 50 per cent of the time.

A student’s access to devices and the internet is a key factor that affected attendance, but there were other issues as well.

Sixteen per cent of all teachers report that students only attended classes half of the time. This is an enormous challenge for teachers.

One teacher notes: “There is an element that is refusing to engage and I am unable to chase up (unlike when they are onsite).”

Teachers are mindful of the increasing pressure on parents and families and found that some students were receiving considerable support at home. However, other students aren’t so fortunate for various reasons, including parents’ work obligations and complex home environments.

One of the factors affecting student learning is the level of support students receive, highlighting the importance of positive home-school partnerships.

Many teachers report greater communication and, in some cases, stronger relationships with parents and carers during COVID-19.

The time at home also gave parents a deeper insight into their child’s capabilities, learning challenges and the work of the teaching profession more broadly.

Back in the classroom

While COVID-19 brought about a period of great uncertainty, the rapid shifts seen across education providers shows us how education might be reimagined in the future.

It’s important to remember that the COVID-19 restrictions were imposed rapidly, with many teachers responding to the situation without sufficient time to plan for what lay ahead. Now that most students are back in the classroom, schools are best placed to identify how students have been affected and how best to remediate any academic, social and emotional concerns.

This will vary from student to student and across school sites depending on the context and the needs of the school community. Large-scale studies like this one are essential in examining how resilience and wellbeing play key roles in supporting beliefs, mindsets, knowledge and reasoning.

But, the immediate priority is to provide additional support for re-engaging vulnerable students that were completely disconnected from schooling during this period.

As one teacher writes: “Good teaching will soon fill any gaps created by online teaching, and teachers that I work with have done incredibly well at adapting to the online environment. It is the social-emotional wellbeing of our young people, particularly those at risk in their homes, that is my biggest concern.”

We must proceed with caution though and ensure that any opportunities arising from the COVID-19 period are evidence-based and research-informed.

Any changes to teaching and learning must be targeted, supported and adequately resourced – ensuring we keep the best interests of our students as the central focus of all that we do.

This article was first published on Pursuit, The University of Melbourne.

Read the original article.

Banner and pictures: Getty Images