In an age of Elsa/Spiderman mash-ups, how to monitor YouTube’s children’s content

The US Federal Trade Commission last week imposed a historic fine of US$170 million (A$247 million) on YouTube for allegedly tracking children’s viewing without parental consent in order to deliver targeted advertising.

This practice of tracking children’s viewing history violates the US Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act, writes Jessica Balanzategui, Swinburne University of Technology

As commission chairman Joe Simons explained, “YouTube touted its popularity with children to prospective corporate clients” while simultaneously refusing to acknowledge “that portions of its platform were clearly directed to kids”.

The commission presented evidence that YouTube has been soliciting brand partnerships and advertising based on its popularity with children. Its report cites a presentation to Mattel where YouTube marketed its platform as “today’s leader in reaching children age 6-11 against top TV channels” and a 2016 presentation to Hasbro where they called themselves “The new ‘Saturday Morning Cartoons’.”

However YouTube’s official position has long been that the platform is not designed for users under 13, circumventing children’s privacy and media regulations.

The commission report cites YouTube’s communication with an advertiser:

We don’t have users that are below 13 on YouTube and platform/site is general audience, so there is no channel/content that is child-directed and no COPPA compliance is needed.

The Federal Trade Commission begged to differ and YouTube’s attempts to discipline its children’s content since then has global implications.

Regulating children’s content

Children’s broadcast content – and the advertising that surrounds it – has long been required to adhere to certain standards. In Australia, this began with 1945’s List of Principles to Govern Children’s [Radio] Programs.

The current relevant legislation is the Children’s Television Standards 2009. This bans all advertising during shows for preschool children, and bans some types of advertising including that featuring “popular characters” for older children. Content cannot be “unduly frightening” or “unduly distessing”, and cannot encourage children to engage in dangerous activities.

The standards include criteria for the quality of programming. It must be “entertaining”, “well produced”, appropriate for Australian children, and “[enhance] the understanding and experience of children”.

But the user-generated nature of YouTube content has meant that a complex ecology of new types of children’s content has evolved outside of these quality frameworks.

More video content is watched by children online than on TV.

More video content is watched by children online than on TV.

from www.shutterstock.com

Disturbing children’s genres

The issues with children’s YouTube go deeper than the recent fine.

On YouTube, genres have formed over time through an enigmatic combination of human and technical factors. Content creators have been incentivised to exploit the algorithm so their videos appear at the top of search results and in auto-play queues.

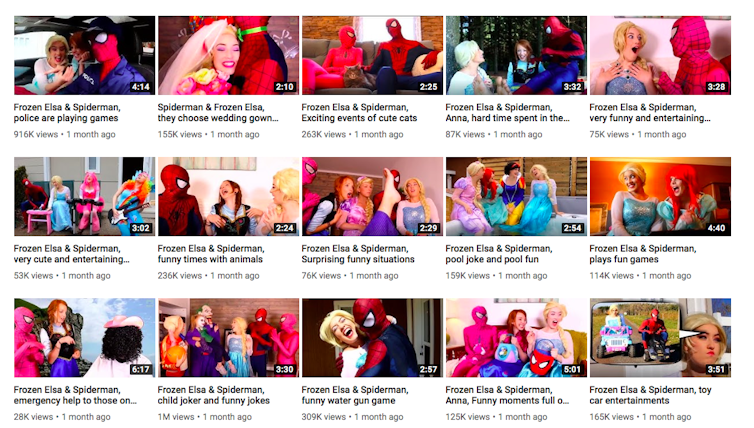

Such practices result in “word salad” video titles like “Spiderman, Frozen Elsa is Taken by Minions! W/Anna & Kristoff, Pink Spidergirl, Maleficient & Candy. Over time, new children’s genres crystallise, like romantic videos featuring Spider-Man and Elsa from Disney’s Frozen.

YouTube channel ‘Superhero-Spiderman-Frozen Compilations’ has over 125 million views.

YouTube channel ‘Superhero-Spiderman-Frozen Compilations’ has over 125 million views.

https://www.youtube.com

Some of the more concerning children’s YouTube genres include dark parodies of popular children’s cartoons, crudely animated or live-action videos featuring adult performers in cheap superhero or Disney character costumes, and “bad baby” videos where pranks are pulled on “naughty” children.

Public controversies about some of these genres have led to the termination of lucrative YouTube channels. One such channel, Toy Freaks had 8.53 million subscribers and documented a father’s pranks on his children.

YouTube has also attempted to demonetise controversial genres by removing ads. Sadistic “prank” content led to criminal sentences of child neglect for parents Michael and Heather Martin of the DaddyOFive channel.

YouTube: The new kids TV

In 2015, in response to the growing popularity of “family entertainment channels” on the platform, YouTube launched YouTube Kids, a dedicated app explicitly oriented at children.

The platform still sat outside of Australian and international children’s content frameworks, although the Australian Association of National Advertisers urged advertisers on YouTube Kids to adhere to their children’s advertising codes. These codes however are self-regulated.

This August, in response to growing criticism of the types of videos readily available to children, YouTube Kids was relaunched as a standalone website which purported to ensure a safer platform.

While YouTube Kids previously grouped together all viewers under 12, the new platform allows parents to select Preschool (under 4), Younger (5-7), or Older (8-12) categories.

These age-based categories will largely be managed by YouTube’s automated filtering and categorisation systems, but will rely on parental reporting of inappropriate videos that slip through filters. While the children’s TV standards and classification frameworks regulate for age appropriate, quality children’s programming on television, such regulation does not extend to online content.

Murky boundaries

With the fine announced just a week after the launch of the new Kids platform, YouTube announced another raft of platform updates.

Creators will now be required to tell YouTube if their content targets children, and the platform will stop serving personalised ads with children’s content. YouTube has committed to using machine learning to more precisely identify child-oriented content.

These new machine-learning strategies will identify children’s content by looking for videos with “an emphasis on kids characters, themes, toys, or games”.

But does this take into account child-oriented genres native to YouTube, like Elsa and Spider-Man romantic mash-ups and bad baby videos, or popular imagery in YouTube children’s content, like syringes and head swapping?

YouTube has transformed the themes, narrative structures, and aesthetics of children’s genres in ways that even the company now struggles to understand.

For these new measures to work, technological solutions need to be grounded in new understandings of children’s screen genres.

Our cultural and policy definitions of children’s content need to catch up with this new frontier.![]()

Jessica Balanzategui, Lecturer in Cinema and Screen Studies, Swinburne University of Technology

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.