Detroit hopes new gifted children initiative avoids equity issues

Michelle Taylor’s first-grader had only been at Chrysler Elementary School for a few months, but already she was bored.

“They didn’t have the tools to support my daughter,” Taylor said. Unsure where else to turn, she had Madeline professionally tested, revealing that she was gifted, writes Kyla Heat in an article first published on Chalkbeat.

After meeting with her daughter’s teacher and principal, Taylor learned there are no gifted programs at Chrysler or any other school in the Detroit Public Schools Community District. As a result, she transferred her daughter to University Liggett, a suburban private school outside Detroit.

‘Introduce gifted education’

The district is now changing its approach to identifying and instructing gifted students in a bid to keep more students like Madeline in the system. Starting in late July, it is partnering with the Roeper School, a private suburban Detroit school, and the Roeper Institute on a two-year initiative to introduce gifted education into four Detroit schools.

The goal is to expand the available options for families while avoiding the issues of inequity that have plagued gifted programs in other cities. Though most students in the district are students of color, officials want to be sure that when they develop a program, savvy parents do not crowd out other qualified families.

“Our goal is to support all learners in a classroom,” said Kimberly Phillips Solomon, executive director for gifted and talented programs for the district.

‘Ensure geographic reach’

Part of the district’s initiative is to restore a gifted education program at Bates Academy. Teachers at several other schools (Communication and Media Arts High School, Pulaski Elementary-Middle School, and Southeastern High School) have received training on gifted learning strategies they can use to improve instruction for all students.

“We will continue to expand gifted training to teachers at the K-8 level and test students for future gifted instructional services,” Superintendent Nikolai Vitti said in a statement. “Our plan is to expand gifted and talented K-8 programming to other K-8 and elementary schools to ensure geographic reach and accessibility throughout the city in the years to come.”

Meanwhile, the district will use universal screening of students when it begins testing sometime next year. The screening relies on non-verbal IQ tests to measure problem solving and critical thinking skills, removing the judgement of teachers and parents. Research has shown that such discretion can block qualified students of color from gifted programs.

‘Many ways to measure mastery’

“If there is an artist, how do we draw in that talent to present the same type of learning instead of a multiple-choice test? There are many ways to measure mastery,” Solomon said.”

Nationwide, eight per cent of white students are classified as gifted, compared with four per cent of black students, according to 2017 statistics from the National Center for Education Statistics.

Other cities have been grappling with similar problems. In Memphis, black students were assigned to gifted programs half as often as white peers with identical test scores. Officials there have proposed universal first-grade screening.

In New York City, officials have expanded the number of gifted programs in low-income neighborhoods and introduced new criteria in areas where few students were passing the required test. Still, black and Hispanic students make up only 27 per cent of the city’s gifted students, though they make up 70 per cent of the city’s students.

New criteria

Once students are identified, though, Detroit faces the challenge of ensuring teachers know what to do next.

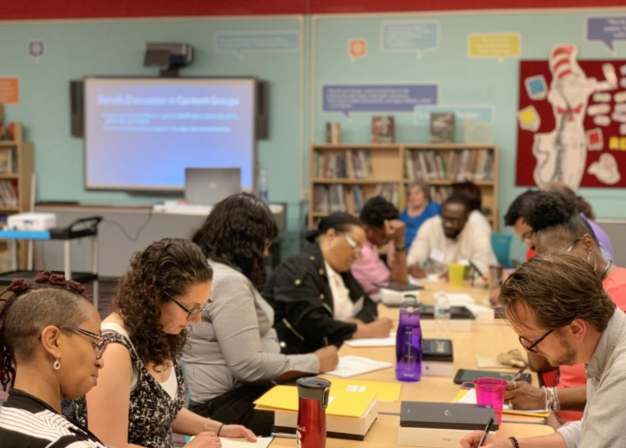

Later this month, 20 district teachers and four Roeper teachers will work with educators from Wayne State University and the College of William and Mary, who will help them learn how to identify and work with gifted students.

Throughout the year, the cohort will continue in-person and online training. That’s made possible by a matching grant to the Roeper Institute of $250,000 from the Edward E. Ford Foundation, a private foundation based in New York, and a $54,000 grant from the Community Foundation for Southeast Michigan.

Orientation was held in mid-June at Bates Academy, one of the district’s premier schools. Although the state recognizes Bates as a school for gifted education, it only offers an accelerated curriculum for English Language Arts, Solomon said.

Properly identified

Teachers broke into small groups to identify traits of gifted children and shared concerns, like how to make sure the students keep up with the work and how to make sure gifted students are properly identified.

Matthew Guyton, who teaches math to 11th-graders at Communication and Media Arts High School, applied to be a part of the cohort because he realized most district schools tend to focus on students who are not performing well, which can leave gifted students feeling isolated.

“I know what it feels like for a teacher to say, ‘Oh, he is smart. He doesn’t need extra help,’” he said. “But, sometimes those are the children that need extra attention.”

‘In tune with my child’

Taylor, whose daughter now attends private school, said she would be willing to take a second look at the district’s new program. But Madeline is thriving and so she is staying put for now, even though the tuition is almost $23,000 a year.

“I would consider moving Madeline back in the future, but it would be after fifth grade,” she said. “It’s important for me to be in tune with my child and her needs when it comes to gifted education.”

This story has been updated to correct information and make clear that teachers at several schools in the district have received training in gifted education, but their schools will not be launching gifted programs next school year.

Chalkbeat is a nonprofit news site covering educational change in public schools. This story was first published on Chalkbeat on July 9, 2019. Sign up for their newsletters here: ckbe.at/newsletters