Shaping sustainable cities for children

The countdown to the Child in the City International Seminar in Antwerp continues. With that in mind, we present the second part of our interview with keynote speaker, Jens Aerts. In this article, Aerts discusses how we can shape sustainable cities for children.

Jens Aerts is an Urban Planning Specialist. He currently supports UNICEF in the development and implementation of its Global Urban Strategy. Aerts is the author of the recent UNICEF publication ‘Shaping urbanisation for children, a handbook on child-responsive urban planning’. He is also a board member of the Vlaamse Vereniging voor Ruimte en Planning (VRP) and a member of the International Society of City and Regional Planners (ISOCARP).

Click here to read part one of our interview with Jens Aerts.

How did the creation of your handbook, ‘Shaping urbanization for children’ come about?

The international development family, including UNICEF, has not been focusing on the most disadvantaged communities in cities for the last twenty years. This had its logic and also made sense from a certain perspective. Until recently there was a shared consensus that extreme poverty and the worst forms of discrimination and deprivations prevailed in rural areas. Urbanization as such was not seen as a major development issue to deal with. This changed when the Sustainable Development Goals were adopted in 2015. This new international framework, that sets the agenda for 2030 for all international development agencies and member states, accounts for the importance of cities and of investment in urban development and local capacities.

My handbook aims to build a bridge between the child rights agenda and the sustainable urban development actors, developing a common language to call for both children’s rights and urban planning principles. As UNICEF itself is not an urban development agency, its strategy is to influence the urban development sector: investing in data and advocacy, developing the capacity of stakeholders and supporting better delivery of urban environments for children. UNICEF’s objective is to sensitize urban stakeholders to children’s vulnerabilities and to show them how impactful urban planning can be. In order to ensure that the handbook would be really inspirational and helpful to develop city-based strategies, a group of experts affiliated with globally active technical organizations supported its conceptualization. Also, a great group of UNICEF sector specialists brought in their views.

How can we help shape sustainable cities for children?

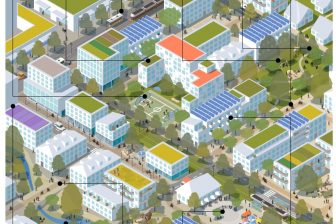

Shaping sustainable cities for children is a matter of working together and developing a common language. Built environment specialists need to refocus on social equity, with ‘E’ of ‘Equity’ referred to as one of the three E’s that stand for a holistic definition of sustainability, as envisioned already more than 30 years ago in the famous Brundtland report. This focus on equity means that urban planners should be 1. measuring spatial equity and working meticulously with data on children, 2. planning and budgeting for all people and thus working with universal design principles and child-responsive norms, 3. engaging with all stakeholders, in particular with children and more vulnerable communities, in technical and social innovation to scale up place-making pilots.

Furthermore, child development and child rights specialists need to acknowledge the spatial aspects of children’s deprivations when advocating for children’s rights in cities. For example, the right to play has been well described in the Convention on the Rights of the Child, but without giving importance to the built environment dimension of this unique right for children, advocacy and programs for more play will not be effective.

Shaping cities for children together means also setting common goals that we can translate into action together, or use to adjust the daily practice in our own discipline. In the handbook on child-responsive urban planning, I developed a benefits framework with five dimensions that are understandable from both the urban planning and the child rights perspective: health, safety, citizenship, environmental sustainability and prosperity. This framework can be refined with detailed indicators to measure the performance of cities and urban development initiatives. It also allows different sectors to collaborate and develop together a robust discourse around specific policies for sustainable cities, such as developing transportation policies that prioritize walking, biking and public transit.

The impact of air pollution on children’s health, the fact that road traffic injuries have become the major cause of death amongst adolescents globally, and the reduction of children’s independent mobility last two decades, highlight the link between transportation and child rights. With the numerous public costs related to car-oriented urban development, it is very clear that a child lens in city planning is the most logical thing there is.

What are the most critical changes that we must make to face the future effectively?

The urgency to address climate change and environmental degradation requires a triple approach: individual behaviours need to change drastically, innovation in the use and re-use of resources should be a priority and policymakers have to enable the needed transitions. This means that the moment of change cannot be postponed until, for example, fossil fuel has been depleted. So the productive economy has to become entirely circular now. Transportation innovations merely focusing on electrification and driverless cars will not address all facets of sustainability. The individual behaviour needs to be changed as well. We need carless drivers instead of driverless cars. And guess what: children don’t drive cars: they crawl, walk and bike.

It might sound counter-intuitive, but in an ageing society, children should even be more central in this process of change. They are the future generation of adults that will bear the responsibility for a growing and ageing society. Children’s ability to grow up as healthy, smart and environmentally conscious citizens is what is at stake for all of us.

What can you tell us about your work with BUUR?

BUUR is an acronym for Bureau for Urbanism but also means ‘neighbor’ in Dutch. It reflects a belief that the city is a compact network of social connections that create shared intelligence, values and engagement towards urban sustainability. BUUR is, for example, an active partner in Leuven 2030, an ambitious multi-stakeholder roadmap to make the city climate-neutral. We also plan and design public spaces, green infrastructure and sustainable mobility networks. Lately, we entered a new phase by looking beyond the traditional deliverables – masterplan, technical design and policy reports. We now put more focus on systematic research and participation with stakeholders. We believe that ambitious sustainability objectives can only be achieved when we generate tailored processes in which all various actors start with sharing knowledge, in order to be able to co-design solutions for complex challenges together. These actors increasingly include ‘unusual’ ones: working on circular economies with waste operators, developing energy landscapes with local municipalities, turning neighbourhoods in car-low and loveable places with children and communities.

What is the biggest challenge to building child-friendly cities at the moment?

I am reluctant to use various adjectives that at the end aim for the same thing: to ensure urbanization to be sustainable, for all current and future citizens. Putting children central in our work as an urban planner is sensible, but not so easy. First of all, fast urbanization with poor local planning capacity forces the few in charge to work in a permanent reactive way, with short-term commitments and weak negotiation mechanisms, making it hard to transform private investment into urban development that is inclusive with shared public space. A survey of the planning profession in the Commonwealth shows that in India there is 1 certified urban planner for 350 000 people, 80 times less than in the UK. And if there is consistent practice and capacity in urban planning, the adults are in charge, often working with old recipes, listening to the loudest voices amongst adult constituents.

Secondly, urban planning has for a long time been focusing on the urban setting as a result of trade-offs amongst sectors in terms of supply of land and building rights, regulated with functional norms and standards, and less on the built environment as an eco-system in which in particularly children adopt behaviours. In that sense, I prefer to speak about the need to build child-responsive cities, which emphasizes that we have to design cities that respond to children’s needs but that are also ‘schools of life’ that teach children everything on sustainability and empowers them to be at the forefront of the urgently needed change. Looking at the current Youth for Climate movement, it is clear that all these engaged children are very conscious and principled in what it takes to save our planet and actually ask for us adults to plan our society and cities in a more consistent way.

A final challenge is that the international development community fails to understand that we should develop the capacity to build a new city capable of housing 1 million people every week during the next 15 years. It is hard to believe that these new urban contexts will cater to children’s needs. On the contrary, without integrated planning capacity on a city level, any health or social investment program will have diminishing returns. In order to avoid being spatially blind, donors and international agencies need to break the silos and rewrite their guidelines if they want to work successfully in urban settings.

What are common misconceptions people have about urbanization? How can we combat these misconceptions and communicate more effectively?

Within the global realm, there is a lot of discourse on the importance of urban planning, however, investment in urban planning is marginal. In Europe, all urban planning mechanisms exist, yet there is also still a kind of abandonment around sprawl, as if it is a necessary condition for economic growth and individual freedom, despite an almost halted demographic growth. This is not sustainable, looking at the science and numbers that illustrate the correlation between urban sprawl, transportation bottlenecks, increased investment costs for public infrastructure and public health.

Children, urban health and urban planning specialists can combat these misconceptions together, by highlighting the impact of sprawl on children and families, including children’s vulnerability to air pollution and transportation infrastructure, children’s isolation and decreasing independent mobility. Together we can call for a child’s right to the city.

What is the best resource for people who want to dive in deeper?

The resource pages at the end of each chapter in the Handbook on child-responsive urban planning will lead to more in-depth information on inspiring initiatives and tools to plan cities with and for children.

Is there anything we’re leaving out here that needs to be addressed?

I was born in Antwerp so this seminar is in a way coming back home. But also looking back at my own childhood. Can you imagine that I biked as a seven-year-old to my school, from home in Deurne-Noord to Borgerhout. With my older brother or with other friends I crossed large roads that at the time had no specific design features to protect cyclists. Unsurprisingly, I got hit by a car at an unprotected passage at the Sterckshoflei that crosses the Rivierenhof. I got hospitalized but kept on biking and a traffic light appeared at this unsafe crossing soon after. Maybe this was when Antwerp started to think about the children in the city?

The Child in the City International Seminar on ‘Children in the sustainable city’ takes place in Antwerp 20-21 May 2019. Spaces are limited so register today. Click here to register.