Modern life offers children almost everything they need, except daylight

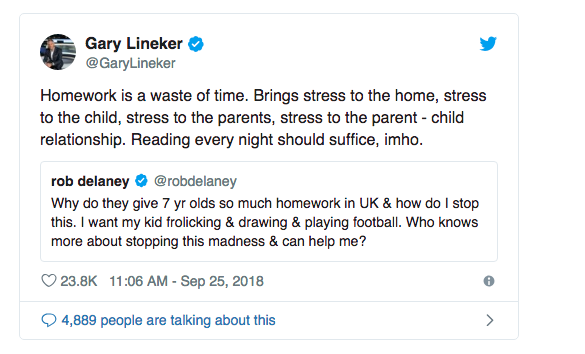

The debate about the volume of homework that children are being given has been bouncing around the opinion pages of broadsheets and red tops in recent weeks after Gary Lineker tweeted that it was “a waste of time”. As names are called and sides are taken in the debate there are much bigger issues at stake than either side is admitting.

As children are given ever more homework we must concede that cramming a child’s day with indoor activities is rolling the dice with their long-term health. As adults, we now spend more time indoors than we have ever done throughout the history of our species. While our indoor habits have implications for our own health, there is more at stake when we encourage this behaviour in our children.

Already, most children are schooled indoors. At the end of their day, there is perhaps an after-school club, tuition or homework to do. When all those are complete, gaming, streaming and social media beckon. As a result, nearly three-quarters of children in the UK spend less time outdoors than prison inmates. A 2016 report concluded that 12% of children in the UK had not been to a park or natural environment at all in the preceding year.

Short-sighted

Outdoor time is essential for children because it helps their eyes, bones and immune systems develop correctly. Evidence is also mounting that it may prevent the onset of food, nut and other allergies.

Babies are born longsighted, with a short eyeball that grows as their bodies do. A healthy eye stops growing when it reaches its optimum shape, but it struggles to do this without access to good quality light – which is only available outdoors. Our eyes are very good at tricking us into believing that our indoor environments are well lit – but even a brightly lit room cannot match the levels of outdoor light, even a cloudy day outside.

Without the correct daylight cues, the eyeball can grow too long, making the child shortsighted; at which point, they will need lenses or surgery to correct their vision. And it’s not just a matter of wearing glasses or paying for some laser surgery. Severe myopia – about a fifth of cases – can lead to blindness in older age. Even though laser surgery can restore vision, the damage done to the eye during development remains, as do the risks.

Several countries in South-East Asia are well ahead of the UK in driving these indoor lifestyles. Most people in Singapore (85%) are shortsighted. Throughout the region, rates are highest among the young. A staggering 96.5% of 19-year-old men in South Korea’s capital, Seoul, are myopic. And while there are a couple of hundred genes at play in the outcome of myopia, the numbers we are seeing are being driven by lifestyle (because it’s believed that genes play only a small to moderate role in the disease’s architecture).

Shortsightedness among the young in the UK has more than doubled in the last 50 years. It is predicted that if nothing is done to curb its spread, half the world’s population will be myopic by 2050.

The sunshine vitamin

Shady living is also in the frame for the return of a disease that was thought to have been eradicated after World War II. Sunlight is essential for our body to make vitamin D. Without it, we cannot absorb calcium and phosphate, which we need for healthy bones, teeth and muscles. Endless indoor hours are contributing to the return of rickets among children in the UK. Rickets causes pain, poor growth and soft or weak bones that bend under the weight of the torso.

Vitamin D deficiency has also been associated with the rise of food and nut allergies, where scientists have noticed that the prevalence increases the further you get from the equator. A lack of outdoor time and lack of exposure to natural environments have also been linked to the huge upturn in allergies more broadly, such as hay fever and asthma, as well as type 1 diabetes. In the case of the latter, it has been suggested that “rapid environmental changes and modern lifestyles” are probably behind the increase.

All of these diseases are telling us that, while urban life offers us many comforts and advantages, it is a lifestyle that is confusing to the modern human body. I know from having researched a book on the way our environment is changing us that we carry DNA which expects us to be performing a wide array of outdoor activities, and not to be spending all our time reading, streaming or playing Fortnite.

Making small changes, such as giving your children more access to daylight, even when it’s cloudy, and encouraging regular physical activity, will set them up for a much healthier future. Getting your children to go out and play is not some hippy notion, it is an essential component of their long term health.

This article was first published on The Conversation. Read the original article here.

![]()