Who is left behind under the new child care subsidy?

Australian families are increasingly relying on childcare but a change in policy may leave those who need it most locked out. The latest Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) Survey reveals Australians are using more formal childcare than ever before.

For families with a child under the age of four, the use of formal childcare has increased by 18 per cent over the last fourteen years. Federal childcare policy has focused strongly on increasing childcare use for two reasons: “[lifting] women’s workforce participation and national productivity”, and more recently, “increasing equity through children’s exposure to high quality [childcare]”. We know that attending formal childcare helps improve school-readiness and adult outcomes for children from disadvantaged backgrounds.

Barriers for the needy

But while the benefits of formal childcare use are greater for disadvantaged children; the take-up of formal childcare services for children from the lowest income quintile is 24 percentage points lower than those from the highest (31 per cent vs 55 per cent). The recent reforms to childcare subsidies may increase this gap in take-up rates even further by creating additional barriers for those who need childcare the most.

The new subsidy introduces an activity test linking the hours of subsidised childcare more closely to work, study or volunteering activities (from here on referred to as ‘work’) of the parent with the least hours of work, which in most cases is the mother’s. The consequence is that children in families with low or no maternal employment hours will now be entitled to fewer hours of subsidised care.

Families previously received 24 hours per week of subsidised childcare regardless of working hours, and 50 hours if each parent in the household worked, trained or studied for at least 15 hours per week. Under the new policy, mothers who work less than eight hours per week with a family income below $66,958 will receive 12 or 18 hours per week.

Subverting equity

And families on higher incomes where the mother works less than four hours will receive zero (see Figure 1). Families where both parents have a higher attachment to the workforce are better off or equally well off as before, unless they work between 15 and 24 hours per week.

By prioritising subsidised care for families with a higher level of maternal employment, the reforms may subvert the second goal of childcare as an instrument to promote equity in child development. Disadvantaged children are more likely to live in families with low or no maternal employment (eight hours per week or less), and so be entitled to fewer childcare hours.

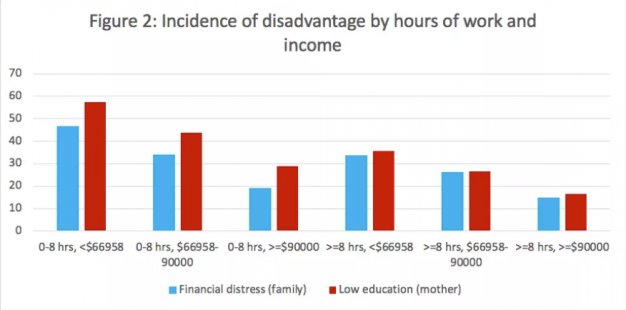

The HILDA data (see Figure 2) shows that, among households with children under the age of four, financial distress is highest for families with a household income less than $66,958 and where the secondary earner is working fewer than eight hours per week. Mothers in these households are also more likely to have a low level of education.

Even among higher-income families, those with mothers working fewer than eight hours per week are more likely to experience disadvantage than families with mothers working more. Under the new scheme, the former group is provided fewer hours of subsidised childcare.

Unintended consequences

Children from disadvantaged families are more likely to be exposed to home environments that are less educationally stimulating than a high-quality formal childcare environment – for example, they are less likely to be read to frequently. A potential, unintended consequence of the new reform is to widen the gaps in school-readiness between advantaged and disadvantaged children.

A key economic rationale for the new policy is to encourage mothers to lift employment levels, but the new Child Care Subsidy may in fact be counter-productive for this goal. The reform doesn’t consider that mothers with little or no attachment to the workforce may have little control over changes in their work schedules or life circumstances. Casual employees, seasonal workers, and those who cycle in and out of unemployment, or suffer from family violence or mental health conditions may need to drop out of the workforce unexpectedly.

Perverse incentives

While the policy includes some safeguards, this could mean losing subsidised childcare hours, and as a result, their childcare space. Although the mother might be able to resume her previous level of work hours, she might be unable to resume the necessary childcare hours. There are relatively few childcare places for very young children in Australia, especially in high-quality, flexible, cost-friendly places located in a capital city. If childcare access proves to be a barrier, then an unexpected, temporary reduction in work hours may lead to a persistently lower level of employment.

Another potentially unintended consequence of the new policy is that it sets up perverse incentives for some families to withhold or reduce employment hours, due to the withdrawal of subsidised childcare hours at certain income thresholds.There are relatively few childcare places for very young children in Australia. Picture: Getty Images

For example, in households where the mother isn’t in the labour force, and where the household income is around the threshold of $66,958, the family is better off if they maintain a household income below, rather than earn just above the threshold. Alternatively, it may make families financially worse-off if they inadvertently earn just beyond the threshold. Over one in ten households with a child aged less than four, may be affected by this threshold since they have an income around the $66,958 threshold (within a $10,000 bracket).

Families where the secondary earner works less than eight hours per week, not only have lower access to subsidised hours of childcare under the new subsidy; they also lose out in terms of the dollar amount of childcare assistance. A recent NATSEM release on the childcare reforms shows the corresponding drop in the dollar amount of childcare assistance for this group of families.

Reducing investments in the early human capital of disadvantaged children may harm them in the long run. Improved child development in the early years is positively associated with higher employment, lower welfare receipt and reduced crime in adulthood. The new childcare policy may increase future fiscal burdens on taxpayers by limiting the developmental potential of disadvantaged children, which affects not just the families in question but also broader society.

This article was first published on Pursuit. Read the original article.

Feature Image: CC Flickr/Fort George G. Meade Public Affairs Office Follow