‘Urban Playground’ makes the case for child-friendly cities – Tim Gill

No parent would ever say ‘this is a great neighbourhood – but I won’t let my child walk to school or play in the local park’. Former Bogotá mayor Enrique Peñalosa grasped this insight when he called children an ‘indicator species’ for cities. It helped him build ambitious policies and programmes that transformed that troubled city, writes Tim Gill, author and children’s play advocate.

In my book, Urban Playground, I expand on Peñalosa’s maxim. I argue that the presence of children of different ages, with and without their parents, being active and visible in the places where they live, shows the quality of urban habitats, just as that the presence of salmon in a river shows the quality of that habitat.

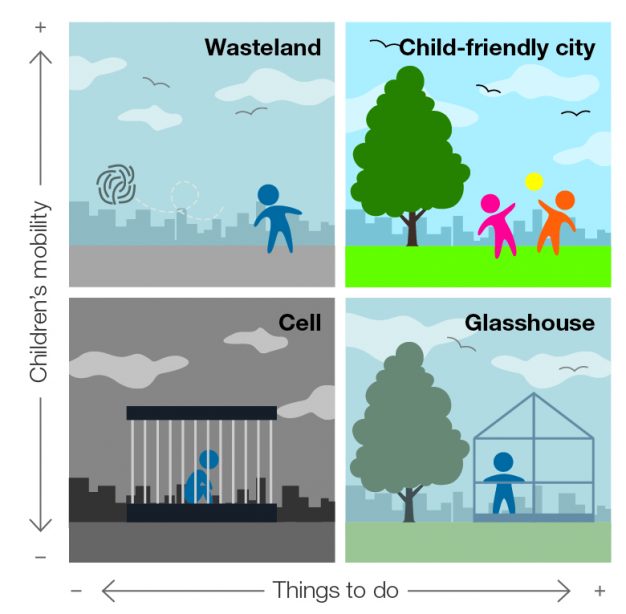

The notion of a broad, healthy diet of childhood experiences is central to child-friendly urban planning. It is encapsulated in the idea of children’s everyday freedoms. In spatial terms, these freedoms have two dimensions. The first dimension focuses on children’s mobility, especially under their own steam. The second dimension is the number and type of spaces and facilities on offer (see Figure 1 below).

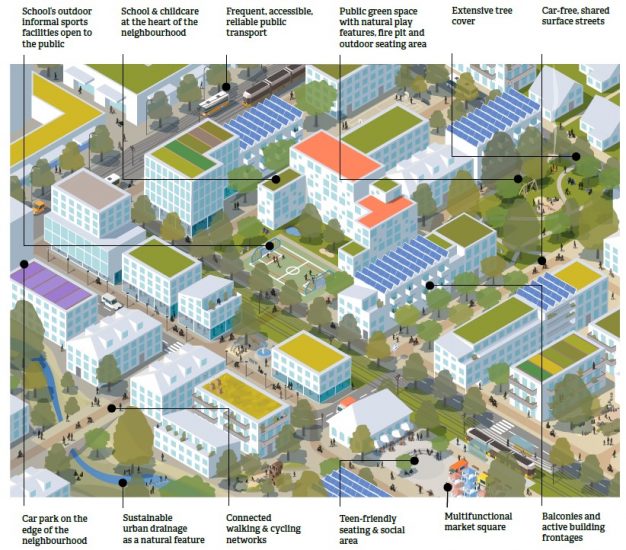

In any ranking of child-friendliness, one neighbourhood that would score highly is Vauban, an essentially car-free masterplanned district in the German city of Freiburg. Vauban is a compact, medium-density mixed-use neighbourhood with a population of around 5,500 residents living in 4-5 storey apartment blocks. Car ownership is particularly low; most roads have no on-street parking and limited car access, and almost all cars are required to be parked in one of three peripheral multi-storey car parks. There are good walking and cycling networks, and a direct tram service to the city centre. With cars out of the way, well-designed, well-overlooked, accessible green public space fills much of the space between the buildings (see Figure 2).

Figure 3 shows an idealized neighbourhood, inspired by (and loosely modelled on) Vauban, which pulls together the key physical features of child-friendly urban planning and design in diagrammatic form. The diagram is offered as a provocation, not a blueprint.

As children tell us all the time, a child-friendly city looks a lot like a sustainable city. A child-friendly city is also a city with a bright future. Any city that fails to attract and retain families is a city whose long-term economic prospects are bleak.

Only the most heartless would say we should ignore children in city building. But why should we seek to involve them directly? They bring to projects an enthusiasm, energy, creativity, and openness to new ideas that can stimulate fresh, radical thinking. Their voices compel us to confront questions about who and what cities are for. And let’s not forget children’s right to participate in decisions that affect them, as enshrined in the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child.

However, involving children is not enough. As adults, we also need to listen, to build on what we already know, and to draw on the expertise and insights of planning and design advocates. Creating vibrant, lively, playful places is complex. We cannot expect children to do it all by themselves.

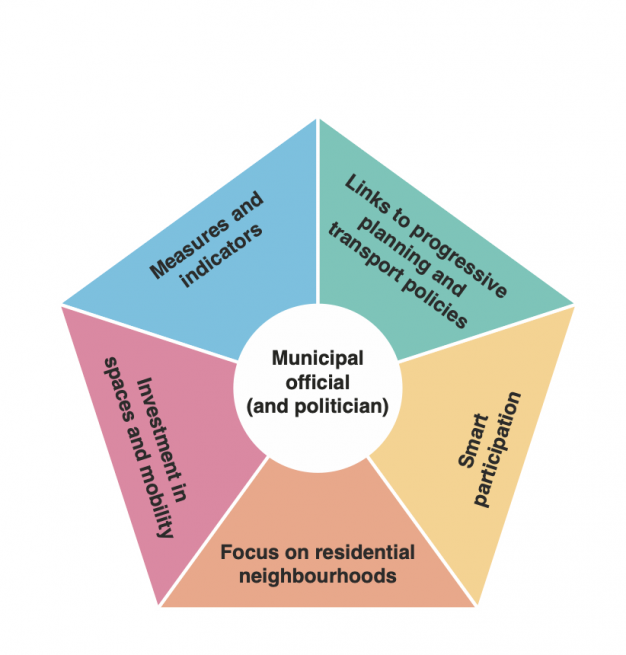

Urban Playground has a clear focus on action at the municipal level, drawing on detailed case studies from cities around the world that have taken the idea of child-friendly urban planning seriously. In almost all the cities I studied, the key catalyst for change was a person in the municipality. Someone with a clear vision and set of values about children and cities, who can negotiate bureaucracies and get things done. Figure 4 offers a hub-and-spoke model for implementing child-friendly planning and design, based on the best approaches in the cities studied.

Urban Playground sets out the basic case for cities to be sustainable, equitable, healthy places for children to live, play and grow up. Resulting schemes will work better, not only for children but also for other groups whose needs and concerns are so often ignored. It also joins the dots between progressive planning and transportation policies and positive health, environmental, community and economic outcomes, and strengthens the arguments for them. It builds the moral case for progressive, inclusive planning. Finally, it show how a children’s lens makes abstract urban policy debates more concrete, meaningful and engaging for ordinary people, helping to overcome narrow vested interests and short-termism.

Looking at planning and design through children’s eyes does not just offer fresh perspectives and a compelling new urban vision. It reveals the best way to set cities on a firm course away from ecological, economic and social decay.

Tim Gill

Tim is an independent scholar and a Design Council UK Ambassador

This article – based on a piece written for Walk the City Prague – includes excerpts from Urban Playground: How child-friendly planning and design can save cities, published by RIBA Publishing and available from good booksellers. For more on the book, head for this web page: http://rethinkingchildhood.com/urban-playground.